This guidance provides a framework for best practice when responding to hoarding concerns for adults with care and support needs within Torbay and Devon.

The guidance should be read in conjunction with the TDSAP Multi agency Safeguarding adult procedures and guidance.

1. Introduction

This guidance sets out a framework for partner agencies to work collaboratively using an outcome focused, solution-based model.

The guidance offers clear guidance to practitioners working with adults who present with hoarding behaviours and has been produced on the best available understanding of the associated challenges for practitioners.

However, partner organisations that provide care and support should also consider their regulatory responsibilities in accordance with Care Quality Commission (CQC) guidance, and if necessary, their own legal advice, in more complex circumstances.

2. Definition of hoarding

Hoarding is the excessive collection and retention of any material to the point that it impedes day to day functioning (Frost & Gross, 1993). Pathological or compulsive hoarding is a specific type of behaviour characterised by:

- acquiring and failing to throw out a large number of items that would appear to hold little or no value and would be considered rubbish by other people

- severe ‘cluttering’ of the person’s home so that it is no longer able to function as a viable living space

- significant distress or impairment of work or social life (Kelly 2010)

3. General characteristics of hoarding

Fear and anxiety: Compulsive hoarding may have started as a learned behaviour or following a significant event such as bereavement. The adult presenting with hoarding behaviours believes buying or saving things will relieve the anxiety and fear they feel. The hoarding effectively becomes their comfort blanket. Any attempt to discard hoarded items can induce feelings varying from mild anxiety to a full panic attack with sweats and palpitations.

Long term behaviour pattern: Possibly developed over many years, or decades, of “buy and drop”. Collecting and saving, with an inability to throw away items without experiencing fear and anxiety.

Excessive attachment to possessions: Adults who hoard may hold an inappropriate emotional attachment to items.

Indecisiveness: Adults who hoard may struggle with the decision to discard items that are no longer necessary, including rubbish.

Unrelenting standards: Adults who hoard may often find faults with others, and may require others to perform to excellence while struggling to organise themselves and complete daily living tasks.

Socially isolated: Adults who hoard may typically alienate family & friends and may be embarrassed to have visitors. They may refuse home visits from professionals in favour of office-based appointments.

Large number of pets: Adults who hoard may have a large number of animals that can be a source of complaints by neighbours. They may be a self-confessed “rescuer of strays”

Mentally competent: Adults who hoard are typically able to make decisions that are not related to the hoarding.

Extreme clutter: Hoarding behaviour may prevent several or all the rooms of an adult’s property from being used for its intended purpose.

Churning: Hoarding behaviour can involve moving items from one part of an adult’s property to another, without ever discarding anything.

Self-care: An adult who hoards may appear unkempt and dishevelled, due to lack of toileting or washing facilities in their home. However, some adults who hoard will use public facilities in order to maintain their personal hygiene and appearance.

Poor insight: An adult who hoards will typically see nothing wrong with their behaviour and the impact it has on them and others.

4. What is hoarding disorder?

Hoarding disorder used to be considered a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In June 2018, the World Health Organisation (WHO) released its new International Classification of Diseases (ICD11) and hoarding is now classified as a medical condition.

Hoarding can also be a symptom of other mental disorders. Hoarding disorder is distinct from the act of collecting and is also different from people whose property is generally cluttered or messy. It is not simply a lifestyle choice. The main difference between a hoarder and a collector is that hoarders have strong emotional attachments to their objects which are well in excess of their real value.

Gender, age, ethnicity, socio-economic status, educational or occupational history or tenure type does not make an adult more susceptible to hoarding behaviours.

Anything can be hoarded, in various areas including the adult’s property, garden or communal areas. However, commonly hoarded items include but are not limited to:

- clothes

- newspapers, magazines or books

- bills, receipts or letters

- food and food containers

- animals

- medical equipment

- collectibles such as toys, video, DVD, or CDs

In line with the preventative agenda in safeguarding, it is important that practitioners consider opportunities for early help interventions when potential risks of hoarding are first recognised when working with an adult.

5. Types of hoarding

There are three types of hoarding:

Inanimate objects: This is the most common. This could consist of one type of object or a collection of a mixture of objects such as old clothes, newspapers, food, containers or papers.

Animal hoarding: Animal hoarding is on the increase. This is the obsessive collecting of animals, often with an inability to provide minimal standards of care. The adult is unable to recognise that the animals are or may be at risk because they feel they are saving them. In addition to an inability to care for the animals in the home, adults who hoard animals are often unable to take care of themselves. As well, the homes of animal hoarders are often eventually destroyed by the accumulation of animal faeces and infestation by insects.

Data hoarding: This is a phenomenon of hoarding. There is little research on this matter and it may not seem as significant and inanimate as animal hoarding, however people that do hoard data could still present with same issues that are symptomatic of hoarding. Data hoarding could present with the storage of data collection equipment such as computers, electronic storage devices or paper. A need to store copies of emails, and other information in an electronic format.

6. Mental capacity and executive function

In some circumstances there may be cause to consider the mental capacity of an adult who is presenting with hoarding and self-neglect behaviours. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a legal framework for such an assessment to be completed and of next steps to be taken depending on the outcome. The information in this section outlines the necessary considerations and legislation that will apply.

The five statutory principles of the Mental Capacity Act (2005)

- Assume Capacity Unless it is established through assessment the person lacks capacity. You should not assume capacity if the person’s behaviour or circumstances raise doubt as to whether they have the capacity to make the decision.

- Maximise Capacity A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them do so have been taken without success

- Unwise Decisions A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he/ she makes an unwise decision

- Best Interest An act or decision under the act for or on behalf of a person who lacks mental capacity must be undertaken in their best interests

- Least Restrictive Can the purpose be effectively achieved in a way that is least restrictive of the persons rights and freedom (this does not mean that no actions are taken)

Assessing mental capacity

An assessment of mental capacity must be time-specific and decision-specific

- Decision-specific About a decision which has to be made in relation to a particular matter. An adult may lack mental capacity in one matter but not another.

- Time-specific A person’s capacity to make a decision is only relevant at the point when the decision needs to be made. This is referred to in the legislation as the ‘material time’. Some decisions are one off, for example to pay a bill, and some involve multiple decision points, for example to accept a care provision each time it is offered. People whose mental capacity fluctuates are likely to struggle with this latter type.

The two-stage test of capacity

The Mental Capacity Act describes the test for mental capacity in the following way:

s.2(1) ‘… a person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material time he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain’

s.2(2) ‘It does not matter whether the impairment or disturbance is permanent or temporary.’

Stage one – the functional test

Is the person able to:

- understand the information relevant for the decision including the merits of choosing one way or another?

- retain this information?

- use or weigh it and make a decision?

- communicate their decision?

If they are unable to perform one or more of the steps they are functionally unable to make the decision. Stage two involves identifying the likely cause of their difficulty.

Stage two – the impairment test

a. Does the person have an impairment or disturbance of the functioning of the mind or brain? There does need to be some evidence of an impairment or disturbance but not necessarily a formal diagnosis.

It may be temporary or permanent but is present at the point the decision needs to be made.

b. If yes, is this impairment likely to be the cause of the functional difficulty identified in stage one?

This link between the practical difficulty and a cognitive impairment is known as the ‘causative nexus’.

If yes to a) and b), the person is deemed to lack mental capacity for this decision.

If after all appropriate help and support has been given to the adult and they are still assessed as unable to make a particular decision at that particular time, any action that is taken MUST be informed by the principles of choice, respect and dignity for the adult concerned, with a clear focus at all times on helping them to achieve the outcomes they want. Areas of risk and concerns MUST be discussed and details of the discussion with the adult around risks must be recorded (defensible decision making).

Practitioners MUST always make every effort to establish whether the adult is being unduly influenced or coerced by another person. For example, if you believe they are being coerced, the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court could apply.

In deciding whether an adult has capacity to make decisions in respect of their items and belongings, relevant information is likely to be that concerning:

((taken from the judgment of HHJ Clayton in AC and GC (Capacity: Hoarding: Best Interests) [2022] EWCOP 3))

(a) Volume of belongings and impact on use of rooms: the relative volume of belongings in relation to the degree to which they impair the usual function of the important rooms

(f) Safe access and use: the extent to which the person (and, if relevant, other residents in the property) are able or not to safely access and use the living areas.

(g) Creation of hazards: the extent to which the accumulated belongings create actual or potential hazards in terms of the health and safety of those resident in the property.

(h) Safety of building: the extent to which accumulated clutter and inaccessibility could compromise the structural integrity and therefore safety of the building.

(i) Removal or disposal of hazardous levels of belongings: that safe and effective removal and/or disposal of hazardous levels of accumulated possessions is possible and desirable because of a “normal” evaluation of utility.

Executive function

Executive functions include planning and organisation, flexibility in thinking, multi-tasking, social behaviour, emotion control and motivation.

Certain disorders of the mind or brain are more widely recognised to be associated with executive dysfunction and include acquired brain injury, dementia, delirium, learning disability, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. However, many other mental disorders can be associated with executive dysfunction including schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and personality disorders. Acute intoxication with drugs or alcohol is also an impairment of the mind or brain.

When executive function is impaired, it can inhibit appropriate decision-making and reduce an adult’s problem-solving abilities. Adults with executive impairment can often present very well in a formal assessment of cognition and mental capacity and articulate with good verbal reasoning skills however they often can “talk the talk but not walk the walk.” Adults with executive impairment are often not aware of any cognitive deficit.

Many of the traits and behaviours observed in executive impairment vary in degree, (they exist on a continuum) and are also observed in the wider population which can make assessment very difficult. Detecting executive impairment and assessing the effect on mental capacity can be very challenging. This can have significant implications because failing to carry out a sufficiently thorough mental capacity assessment in these situations can expose an adult at risk to substantial risks. Speaking with carers, friends who know the adult, and gathering information from any other agencies that the adult may be known to such as housing, environmental and emergency services, may provide clarity of the potential mismatch.

A key to the relationship between executive function problems and a person’s mental capacity is the extent to which they have insight into their practical difficulties. A person who does not understand that in practice they make a decision about what to do but don’t do it, is failing to understand a key piece of ‘relevant information’. They will struggle to consider options for support with their difficulties if they do not recognise what is really happening.

Distinguishing between unwise decision making and decisions affected by executive impairment can also pose a challenge. It is imperative that the assessor uses the functional test, to consider the process of how the adult reached that decision.

Fundamentally, in unwise decision making, the adult is fully aware but consciously disregarding or giving less weight to certain facts relevant to the decision. In executive impairment, the adult cannot access and integrate the correct pieces of information and use them in a meaningful way to make the decision. Repeated assessments help to get a better sense of any repeated mismatch between the adult’s words and actions. Although there is no case that is determinative of this point, Essex Chambers’ guidance states that:

‘You can legitimately conclude that a person lacks capacity to make a decision if they cannot understand or ‘use and weigh’ the fact that they cannot implement in practice what they say in assessment they will do.’

BUT you can only reach such a finding where there is clearly documented evidence of repeated mismatch. It is therefore important that professional curiosity is applied in situations where executive functioning is questioned. This more longitudinal and holistic assessment of mental capacity is essential in detecting the more subtle effects of executive impairment on decision making. However, it is clear that this approach does not sit neatly with the very distinct legal definition of a determination of capacity being decision and time specific, highlighting one of the difficulties with the current legal framework.

7. Information sharing

All health and social care practitioners and partners have a common law duty of confidentiality within their work with adults at risk. They also have a duty to process personal data in line with the Data Protection Act 2018; UKGDPR and to comply with the Caldicott principles. These are a set of requirements that ensure information regarding people who use services is treated with sensitivity to maintain its confidentiality.

All partner agencies need to ensure where it is decided that it is appropriate to share information regarding properties with concerning levels of clutter, that this is justified and proportionate. All information should be transferred in a secure format.

Information will be shared within and between partner organisations in line with the principles set out below.

- Adults have a right to independence, choice and self-determination. This right extends to them being able to have control over information about themselves and to determine what information is shared. Even in situations where there is no legal requirement to obtain written consent before sharing information, it is good practice to do so.

- The adult’s wishes should always be considered, however, protecting the adult at risk establishes a general principle that an incident of suspected or actual abuse can be reported more widely and that in doing this, some information may need to be shared among those involved.

- Information given to an individual practitioner belongs to the organisation and not to the individual employee. An individual employee cannot give a personal assurance of confidentiality to an adult at risk. Difficulties in working within the principles of maintaining the confidentiality of an adult should not lead to a failure to take action to protect the adult from abuse or harm.

- Confidentiality must not be confused with secrecy, that is, the need to protect the management interests of an organisation should not override the need to protect the adult.

- Employees reporting concerns at work (whistle blowing) are entitled to protection under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

The decisions about what information is shared and with who will be taken on a case by-case basis. Whether information is shared and with or without the adult at risk’s consent, the information shared should be:

- necessary for the purpose for which it is being shared

- shared only with those who have a need for it

- accurate and up to date

- shared in a timely fashion

- shared accurately

- shared securely

For further guidance regarding information sharing see the TDSAP Information Sharing protocol.

Where there are concerns regarding abuse or neglect and an adult refuses a needs assessment, Section 11 of the Care Act 2014 provides a legal framework to carry out a needs assessment. This can enable a multi-agency assessment of risks and information sharing within a safeguarding response to explore a robust risk management plan and identify any required actions and proportionate next steps.

As a matter of practice, it will always be challenging to carry out an assessment fully where an adult with mental capacity has declined. Practitioners and managers should record all the steps that have been taken to undertake a needs assessment including involving the adult and any Carer, as required by section 9(5) of the Care Act 2014, and assessing the outcomes that the adult wishes to achieve in day to day life and how their needs could be met that may contribute to the achievement of those outcomes, as required by Section 9(4) of the Care Act 2014.

In light of the adult continuing to decline or due to capacitated life-style choices, the result may either be that it has not been possible to undertake an assessment fully or the conclusion of the needs assessment is that the adult declined to accept the provision of any care and support. However, case recording should always be able to demonstrate that all necessary steps have been taken to carry out a needs assessment that are required, reasonable and proportionate in all the circumstances. This should include as appropriate a mental capacity assessment demonstrating that executive functioning has been explored as far as is possible.

As part of the assessment process, it should be demonstrated that appropriate information and advice has been made available to the adult, including information and advice on how to access care and support. In circumstances where an adult has declined an assessment and support and remains at high risk of serious harm as a result, a Section 42(2) safeguarding enquiry should be undertaken.

8. Fire safety

The property of an adult who has clutter in their home can pose a significant risk to themselves and everyone who lives in the home as well as to adults and children living in neighbouring properties. The clutter can result in exit routes becoming blocked making safe evacuation in case of a fire very difficult and in some circumstances impossible resulting in death. When doors cannot be closed and where flammable items such as newspapers or cardboard are present there is risk of fire spreading more quickly which further reduces the chances of safe exit from the property.

A home safety visit should be requested from Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service if the hoarding level presents fire risks. This request can be made at Request a home safety visit | Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service

To make an urgent home safety visit referral please call 0800 05 02 999.

As part of a preventative approach, a practitioner can support an adult to engage with a home safety check from Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service, which can be accessed online: Online home safety check | Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service.

There may be circumstances when an adult does not consent to a home safety visit. A practitioner can submit information, as part of Devon and Somerset Fire Rescue Service’s commitment to keeping people safe in their homes, which will save vital time for fire crews attending an incident. This can be submitted at Partner information risk capture | Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service.

9. Environmental health statutory duties

There are some powers available to environmental health officers that may be applicable in hoarding circumstances. Their use should be considered in conjunction with other aspects of this guidance.

Public Health Act 1936

Section 79: Power to require removal of noxious matter by occupier of premises

The Local Authority (LA) will always try and work with a householder to identify a solution to a hoarded property, however in circumstances where the resident is not willing to co-operate the LA can serve notice on the owner or occupier to ‘remove accumulations of noxious matter’. Noxious is not defined, but usually is ‘harmful, unwholesome’ or very unpleasant e.g. something very smelly or offensive to the point of arousing disgust. No appeal available and if not complied within 24 hours, the LA can do works in default and recover expenses.

Section 83: Cleansing of filthy or verminous premises

Where any premises, tent, van, shed, ship or boat is either;

a) filthy or unwholesome so as to be prejudicial to health; or

b) verminous (relating to rats, mice other pests including insects, their eggs and larvae)

LA serves notice requiring clearance of materials and objects that are filthy, cleansing of surfaces, carpets etc within 24 hours or a reasonable period of time. If not complied with, Environmental Health (EH) can carry out works in default and charge. No appeal against notice but an appeal can be made against the cost and reasonableness of the works on the notice.

Section 84: Cleansing or destruction of filthy or verminous articles

Any article that is so filthy as to need cleansing or destruction to prevent injury to persons in the premises, or is verminous, the LA can serve notice and remove, cleanse, purify, disinfect or destroy any such article at their expense.

Prevention of Damage by Pests Act 1949

Section 4: Power of LA to require action to prevent or treat Rats and Mice

Notice may be served on owner or occupier of land/ premises where rats and/ or mice are or may be present due to the conditions at the time. The notice may be served on the owner or occupier and provide a reasonable period of time to carry out reasonable works to treat for rats and/or mice, remove materials that may feed or harbour them and carry out structural works.

The LA may carry out works in default and charge for these.

Environmental Protection Act 1990

Section 80: Dealing with Statutory Nuisances (SNs)

SNs are defined in section 79 of the Act and include any act or omission at premises that prevents the normal activities and use of another premises, including the following:

Section 79

(1) (a) any premises in such a state as to be prejudicial to health or a nuisance

(e) any accumulation or deposit which is prejudicial to health or a nuisance

(f) any animal kept in such a place or manner as to be prejudicial to health or a nuisance

The LA serves an Abatement Notice made under section 80 to abate the nuisance if it exists at the time or to prevent its occurrence or recurrence. LA can then either prosecute or carry out works in default.

10. Safeguarding children

The Children Act (1989) and the Children Act 2004 is the legislation that underpins child welfare law in England and Wales. Safeguarding children refers to protecting children from maltreatment, preventing the impairment of their health or development and ensuring that they are growing up in circumstances consistent with the provision of safe and effective care. Growing up in a property with concerning levels of clutter can put a child at risk by affecting their development and in some circumstances, leading to the neglect of a child, which is a safeguarding issue.

The needs of the child at risk must come first and any actions considered and taken must reflect this. Therefore, where children live in the property, a safeguarding concern should be raised immediately with the relevant multi-agency safeguarding hub.

Regarding children in Torbay, you can make a referral to the Torbay Multi-Agency Safeguarding hub

Regarding children in Devon, you can make a referral to the Devon Multi-Agency Safeguarding hub

11. Adult at risk

This guidance recognises that either the adult who is presenting with hoarding behaviours or someone living with them may be an ‘adult at risk’. There may be a safeguarding concern about any adult if they are at risk of harm due to the living circumstances. If in doubt, discuss the issue with a manager or raise a safeguarding adult concern referral.

Taking a trauma informed or shame informed approach

We recognise that previous, and possibly current, experiences of trauma may affect how adults present in hoarding and self-neglect circumstances.

This needs to be considered within the context of their presentation. (See Appendix 2 Guidance questions for practitioners). It is imperative that practitioners are aware of the impact that language can have on the adult. It is therefore advised that practitioners should be sensitive with use of language. For example, the terms hoarding or hoarder may reinforce experiences of trauma and shame and therefore terms such as clutter levels may be more appropriate. Please see ‘Keith’s Story’ in Appendix 5.

Overarching this guidance is the fundamental belief that all agencies should provide care respecting a Human Rights based approach. This includes respect that adults want to be involved in decisions that affect their lives, that there is accountability and monitoring of how adults’ rights are affected, that services are non-discriminatory (and further to that those who face the biggest barriers should have their needs prioritised), that everyone should understand their rights and that approaches should be grounded in the legal rights that are set out in domestic and international laws.

12. Multi agency response

It is recognised that hoarding is a complex condition and that a variety of partner agencies will come into contact with the same adult. Not all adults will receive support from statutory services such as Mental Health.

Any professional working with an adult who may have, or appear to a have, a hoarding condition should ensure they complete the Practitioners Hoarding Assessment (see Section 22) and use the clutter image rating tool kit to decide on the most appropriate next steps.

Any professional calling a multi-agency meeting can use the agenda template in Appendix 1.

Where there are circumstances of complexity or high risk these should be escalated within your own organisation to ensure appropriate actions are taken and governance oversight; as well as that appropriate support is available to practitioners.

Occasionally, situations arise when practitioners in one organisation may feel that the decision made by a practitioner from another organisation regarding risk is not appropriate. Working together effectively depends on an open and honest approach between partner organisations.

To resolve any potential professional disagreements relating to the safety of adults at risk, please refer to the TDSAP escalation protocol to guide next steps.

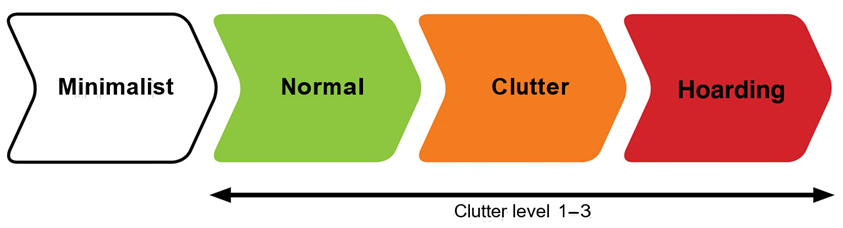

Continuum of hoarding behaviour

13. Flowchart for applying the Clutter Image Rating Tool

The flowchart attached sets out the process clearly. If in doubt, please ask your supervisor or manager for assistance.

Please use the clutter image rating in the next section to assess what level the adult’s hoarding concern is at:

- Images 1–3 indicate level 1

- Images 4–6 indicate level 2

- Images 7–9 indicate level 3

Then refer to the clutter assessment tool (section 16 below) to support your consideration of appropriate actions. Record all actions undertaken in agency’s recording system, detailing conversations with other professionals, actions taken and proposed action.

It is beneficial to complete the clutter image rating tool together with the adult, enabling them to evaluate each room and assign a rating. This collaboration enables the practitioner to discuss the ratings and address any differences in opinion. Working on the clutter index jointly can also foster an empowering approach and promote a sense of inclusion.

14. Assessment tool guidelines

1. Property, structure, services and garden area

- Assess the access to all entrances and exits for the property. (Note impact on any communal entrances & exits). Include access to roof space.

- Does the property have a smoke alarm?

- Visual Assessment (non-professional) of the condition of the services within the property e.g. plumbing, electrics, gas, air conditioning, heating, this will help inform your next course of action.

- Are the services connected?

- Assess the garden size access and condition

2. Household functions

- Assess the current functionality of the rooms and the safety for their proposed use. e.g. can the kitchen be safely used for cooking or does the level of clutter within the room prevent it.

- Select the appropriate rating on the clutter scale.

- Please estimate the % of floor space covered by clutter

- Please estimate the height of the clutter in each room

3. Health and safety

- Assess the level of sanitation in the property.

- Are the floors clean?

- Are the work surfaces clean?

- Are you aware of any odours in the property?

- Is there rotting food?

- Does the adult use candles?

- Did you witness a higher than expected number of flies?

- Are household members struggling with personal care?

- Is there random or chaotic writing on the walls on the property?

- Are there unreasonable amounts of medication collected? Prescribed or over the counter?

- Is the adult aware of any fire risk associated to the clutter in the property?

- Do any rooms rate 7 or above on the clutter rating scale?

4. Safeguard of children and family members

- Are there any other people in the household that you are concerned about including children?

- Is there a person in a caring role that may require a Carer’s assessment or support from Carers services?

5. Animals and pests

- Are the any pets at the property?

- Are the pets well cared for; are you concerned about their health?

- Is there evidence of any infestation? For example, bed bugs, rats or mice.

- Are animals being hoarded at the property?

6. Personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Following your assessment do you recommend the use of PPE at future visits? Please detail

- Following your assessment do you recommend the adult is visited in pairs? Please detail

Level 1 – Clutter image rating 1-3 table

Level 2 – Clutter image rating 4-6 table

Level 3 – Clutter image rating 7-9 table

15. Guidance for practitioners

Hoarding insight characteristics

Use this guide as a baseline to describe the adult’s attitude towards their hoarding. Provide additional information in your referrals and reports to enable a tailored approach that is relevant to the adult.

Good or fair insight:

The adult recognises that hoarding-related beliefs and behaviours (relating to difficulty discarding items, clutter or excessive acquisition) are problematic. The adult recognises these behaviours in themselves.

Poor insight

The adult is mostly convinced that hoarding-related beliefs and behaviours (relating to difficulty discarding items, clutter or excessive acquisition) are not problematic despite evidence to the contrary. The adult might recognise a storage problem but has little self-recognition or acceptance of their own hoarding behaviour.

Absent insight

The adult is convinced that hoarding-related beliefs and behaviours (relating to difficulty discarding items, clutter or excessive acquisition) are not problematic despite evidence to the contrary. The adult is completely accepting of their living environment despite it being hoarded and possibly a risk to health.

Detached with assigned blame

The adult has been away from their property for an extended period. The adult has formed a detachment from the hoarded property and is now convinced a 3rd party is to blame for the condition of the property. For example, a burglary has taken place, squatters or other household members.

16. My Support Agreement

As part of the overall assessment of an adult’s hoarding behaviours, completion of the Readiness to Change Questionnaire is a key aspect as it will help to determine an adult’s insight and motivation to understand the impact and work collaboratively with professionals. The My Support Agreement (Appendix 3) helps to set out a structure with the adult or their family to clarify appointments and expectations of the need to work in partnership to bring about positive changes.

17. Risk assessment and personal protection equipment

When attending properties falling into the Moderate to High Clutter Ratings practitioners MUST take every appropriate precaution relating to their own personal safety in relation to personal protection equipment and consider whether a joint visit is required. Practitioners should refer to their organisational risk policy for further guidance.

18. Supervision and support

Supporting compassionate leadership across partner agencies should be core to professional practice. We understand that working with the complexity of hoarding behaviours and self-neglect can create feelings of vicarious trauma to practitioners involved. Support should be available from line managers through supervision and each partner agency’s well-being services.

19. Practitioners Hoarding Assessment

This assessment should be completed using the information you have gained using the Practitioners Guidance Questions. Complete this review away from the adult’s property and in conjunction with the Assessment Tool Guidelines (see section 16). Text boxes will expand to allow further text.

Acknowledgement

TDSAP would like to thank the Torbay Hoarding Multi Agency Group for giving permission to adapt their ‘Multi Agency Hoarding Protocol’ and ‘Practitioners Assessment Toolkit’ to produce this guidance for all TDSAP partner agencies.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Multi-agency meeting template

Appendix 1 For use with Level 3 (clutter image rating 7-9

Appendix 2 Guidance Questions for Practitioners

Appendix 2 Guidance Questions for Practitioners

Appendix 3 My Support Agreement

Appendix 3 My Support Agreement

Appendix 4 Readiness for Change Questionnaire

Appendix 4 Readiness for Change

Appendix 5 Organisations offering support

Appendix 5 Organisations offering support

Appendix 6 Statutory Advocacy

Appendix 7 Legal interventions

Appendix 7 Legal interventions