This guidance provides a framework for best practice when responding to self-neglect concerns for adults with care and support needs within Torbay and Devon.

The guidance should be read in conjunction with the TDSAP Multi agency Safeguarding adult procedures and guidance.

Foreword

This guidance is a reference for practitioners working to support adults who are experiencing self-neglect. It is envisaged that this will provide an understanding of self-neglect in the context of safeguarding adults and inform a proportionate response in accordance with the Care Act 2014.

Self-neglect and hoarding frequently feature in national and local Safeguarding Adults Reviews and as a partnership we are determined to embed the lessons we have learnt which have informed this guidance. We know that crucial to effective support is the ability to engage and build a rapport with adults, explore their lived experience and develop relationships of trust. This is very much in keeping with the ethos and principles of making safeguarding personal and our duty to promote the adult’s wellbeing.

This guidance applies to all practitioners from Torbay and Devon Safeguarding Adults Partnership (TDSAP) partner organisations and demonstrates a commitment that all partners will fully engage in partnership working to achieve the best outcome for the adult and the wider community, while meeting the requirements and duties of individual partner organisations. This supports the vision of the TDSAP which is ‘Ensuring every adult in Torbay and Devon is able to live in safety, free from abuse and neglect. Everyone who lives or works in Torbay and Devon has a role to play.’

Torbay and Devon Safeguarding Adults Partnership May 2025

1. Introduction

Self-neglect is widely recognised as a significant public health concern and social need that can have profound consequences for health and well-being. This guidance will include learning from published Safeguarding Adults Reviews (SARs) and aligns with the legal framework of the Care Act 2014.

The Care Act (2014) advocates a person centred rather than a process driven approach, and Torbay and Devon partners strive to achieve this in all aspects of professional practice. This guidance promotes a proportionate person-centred response to self-neglect while supporting an adult who may be at risk.

The guidance will also provide additional support to partner organisations and their employees to make the shift in culture and practice necessary to achieve the Care Act 2014 vision for adult safeguarding where:

- safeguarding is the responsibility of all partner agencies

- a whole-system approach is developed

- safeguarding responses are proportionate, transparent and outcome-focused

- the person’s wishes are at the centre

- There is an emphasis on prevention and early intervention

The guidance will provide support to practitioners to work in partnership for early intervention which will enable them to achieve creative and proportionate interventions that respect the adult’s right to self-determination; balancing empowerment and the practitioner’s duty to protect health and well-being.

Aim of the guidance

This guidance aims to support practitioners working across all partner agencies in Torbay and Devon to recognise the implications of self-neglect on the health and wellbeing of adults and their families who are affected. Partner organisations are encouraged to work in partnership with adults, communities and other organisations to raise awareness of self-neglect and hoarding behaviours by sharing information appropriately, providing advice and support as required.

Our ambition

The guidance builds on the already important work that has been started by the partners of the TDSAP who should ensure they work collaboratively to protect adults who have care and support needs and are at risk. The Care Act 2014 has created a legal framework so that organisations and individuals with responsibility for adult safeguarding can agree on how they can best work collaboratively and what roles they must fulfil to keep adults at risk safe. This guidance aims to strengthen and encourage a more preventative approach to circumstances of self-neglect.

Our vision

Is for all professionals to be supported to recognise and respond to all adults who may self-neglect and for their interventions to be person centred, trauma informed, responsive, sensitive and proportionate.

2. Guidance summary

Concern about an adult who has care and support needs who is self-neglecting

In all circumstances:

- attempt to reduce any immediate risks

- remember the importance of building trust and rapport, rather than having an overreliance on assessments

- consider and assess mental capacity, where appropriate

- be professionally curious, listen and find out more from the adult

- be mindful of the adult’s ability in terms of pace

- relationship building with the adult is key

- provide continuity

- identify key individuals and agencies involved

- share information and work together

- record risks and actions taken

- be flexible, persistent and use a trauma informed approach

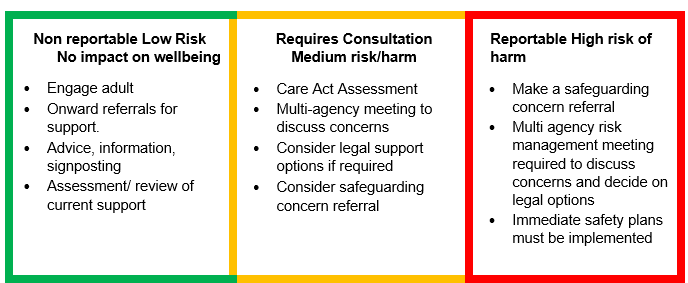

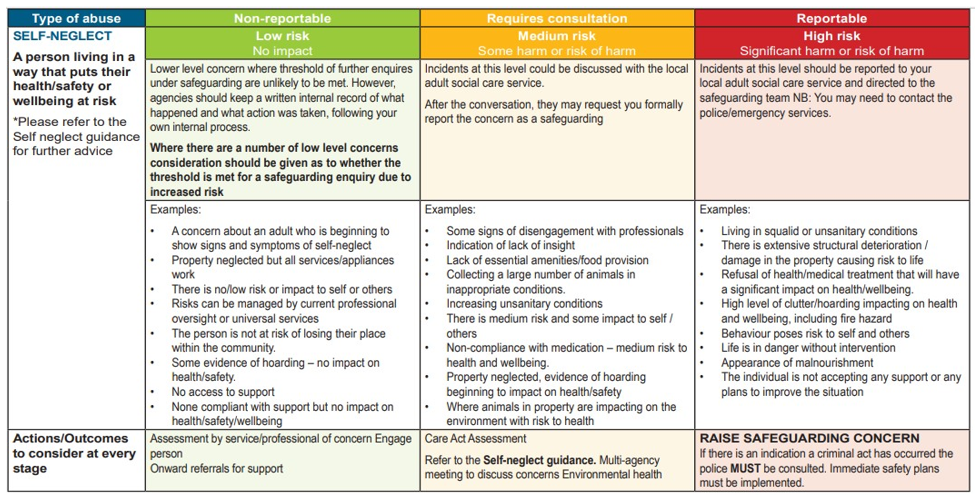

Identify the level of harm or risk (using section 6 – identifying the level of risk or harm to the adult)

At all levels:

- seek advice and guidance from managers and partners

- ensure robust supervision and support is in place

- consider the safety of other adults and children – ‘Think Family’

Where there are concerns about an adult with care and support needs who may be self-neglecting, an appropriate assessment of the adult’s needs for care and support must always be considered.

There are some occasions where an adult safeguarding concern referral about self-neglect should be made, in accordance with Section 42 of the Care Act 2014, such as when there are issues and complexities around the existing support systems in meeting the needs of the adult, there appears to be significant risks from self-neglect or when partner agencies have been involved and it has been identified the adult still has clear needs that have not yet been met.

Always consider risks to other adults or children affected by the adult’s self-neglect or needs and make a safeguarding concern referral as per your organisation’s safeguarding policy

3. What is self-neglect?

The care and support statutory guidance defines self-neglect as:

‘… a wide range of behaviour neglecting to care for one’s personal hygiene, health or surroundings and includes behaviour such as hoarding. It should be noted that self-neglect may not prompt a section 42 enquiry. An assessment should be made on a case by case basis. A decision on whether a response is required under safeguarding will depend on the adult’s ability to protect themselves by controlling their own behaviour. There may come a point when they are no longer able to do this, without external support.’

Self-neglect can be challenging for practitioners to address, because of the need to find the right balance between respecting an adult’s autonomy and fulfilling a duty to protect the adult’s health and wellbeing.

Indicators of self-neglect

- Poor personal hygiene.

- Unkempt appearance.

- Lack of essential food, clothing or shelter.

- Social withdrawal from family, community or support networks.

- Malnutrition or dehydration (or both).

- Living in squalid or unsanitary conditions.

- Neglecting household maintenance.

- Hoarding.

- Non-attendance at health or other care appointments.

- Unable to take medication or treat illness or injury.

- Unable to protect self from harm or abuse.

- Morbid obesity where there may be links to self-neglect and trauma, resulting in less ability to self-care.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Rachel)

Concerns were raised with several partner agencies over a period of time. There was no apparent recognition of the level of self-neglect and the need for a multi-agency response.

There was also no recognition of the patterns of self-neglect and the deteriorating situation.

What can lead to self-neglect

Adults may self-neglect and/or hoard for a number of reasons and there can be a variety of triggers (this list is not exhaustive):

- Brain injury, dementia or other mental disorder.

- Self-care is one of many competing priorities.

- Obsessive compulsive disorder or hoarding disorder.

- Addiction to substances impacting on executive functioning.

- Childhood neglect, childhood trauma or adverse childhood experiences with trauma lasting through to adulthood which impact upon their current decision making.

- Trauma or life changing events experienced during adulthood, for example, bereavement.

- Physical illness which has an effect on abilities, energy levels, attention span organisational skills or motivation.

- Reduced motivation as a side effect of medication.

- The loss of independence as a result of an accident, trauma, major ill health or frailty.

Marginalised and under-represented groups

There are some groups in our community that may be marginalised and under-represented who, because of their circumstances, may present at higher risk of self-neglect.

In line with the Equality Act 2010 it is essential to recognise anyone who may have protected characteristics under this legislation and ensure that reasonable adjustments are made accordingly.

Those with a learning disability may present with increased risk of abuse and neglect as may those adults where risks of abuse interconnect such as race, gender and other forms of possible disadvantage (intersectionality).

Interpersonal and gender-based violence and abuse

The Devon Interpersonal and Gender-based Violence and Abuse Partnership Board (IG-BVA) and the Torbay Domestic Abuse and Sexual Violence Executive Group work towards improving outcomes for victims and survivors of interpersonal and gender-based violence including domestic abuse, sexual violence and abuse and Violence against Women and Girls. They recognise that IG-BVA will have unique impact on individuals depending on their circumstances, needs and experience of inequalities and oppressions.

The traumatic impact of IG-BVA is far reaching and can be long lasting. This may manifest itself at any point in someone’s life, even years after the event occurred. Trauma may display, amongst other presentations, as a person being unable to meet their own basic needs. This can be as a result of low of self-worth and poor self-esteem resulting in individuals not being able to seek, accept or receive support.

For example, a victim of domestic abuse may find self-care difficult due to the impact of the resulting trauma whilst women experiencing multiple disadvantages, such as homelessness, mental health difficulties and experiences of abuse, may present as neglecting themselves and become vulnerable to a cyclic pattern of violence and abuse including sexual exploitation.

A victim of financial and/or economic abuse may not have the means to self-care whilst an adult subject to emotional abuse may present with mental health needs that result in self-neglect.

It is important to note that cause and effect are often undeterminable when we look at IG-BVA because of the longstanding and compounding effects of trauma. Practitioners, in their engagement with adults, need to ensure their response is trauma informed, be sensitive to the relation between self-neglect and low self-worth, be aware that an apparent self-neglect presentation may have as a root cause current and historical experiences of IG-BVA and the resulting trauma. This, in turn, may also make adults more vulnerable to violence and abuse including coercive control. Practitioners should always take a non-judgemental and curious approach to routinely enquire about IG-BVA.

A collaborative approach with the adult into the reasons for self-neglect is required to determine if any form of abuse has taken place and what kind of support they require. An approach where there is ‘professional curiosity’ should be used (Appendix 11)

Trauma-informed practice

Adults who experience self-neglect may decline help from others; in many circumstances adults may express they do not require support. Trauma–informed practice increases practitioners’ awareness that experiences of trauma can have an impact on felt safety. There can exist a mistrust of agencies and professionals, which creates barriers for adults to accessing and/or accepting support. Any intervention should seek to minimise the risks while respecting the adult’s choices.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

When faced with service refusal, a full exploration of what may lie behind a person’s refusal to engage; shame and trauma (rather than lifestyle choice) can lie behind refusals to engage.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Erik)

It is important to consider why adults with complex needs do not always engage with practitioners who seek to support them. Taking a trauma informed approach will support engagement and a focus on how communication methods can be tailored to the person to ensure their understanding.

Learning from National Reviews (SAR Gayle22)

This review found a significant link between the development of morbid obesity with adverse experiences in childhood. It also found that the safeguarding implications of self-neglect alongside adult morbid obesity were little understood. See Appendix 5 for further information.

Risks associated with self-neglect

Social isolation and self-neglect can impact upon physical and mental wellbeing. Other risks can include:

- falls risk

- the risk from poor housing structures and lack of repairs

- nutritional risks

- risk from insanitary conditions

- risk of infection or vermin

- environmental risks to others

- risk of losing accommodation and becoming homeless

- risk of exploitation by others

- fire risks

Fire safety

Some adults who self-neglect may also accumulate clutter in their homes which can pose a significant risk to themselves and everyone who lives in the home as well as to adults and children living in neighbouring properties.

The clutter can result in exit routes becoming blocked making safe evacuation in case of a fire very difficult and in some circumstances impossible resulting in death.

When doors cannot be closed and where flammable items such as newspapers or cardboard are present there is risk of fire spreading more quickly which further reduces the chances of safe exit from the property.

A home safety visit should be requested from Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service if the hoarding level presents fire risks. This request can be made at Request a home safety visit | Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service.

To make an urgent home safety visit referral please call 0800 05 02 999.

As part of a preventative approach, a practitioner can support an adult to engage with a home safety check from Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service, which can be accessed online: Online home safety check | Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service.

There may be circumstances when an adult does not consent to a Home Safety Visit. A practitioner can submit information, as part of Devon and Somerset Fire Rescue Service’s commitment to keeping people safe in their homes, which will save vital time for fire crews attending an incident. This can be submitted via this link: Partner information risk capture | Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Alec)

It is critical that risk assessments are undertaken in circumstances of self-neglect. Practitioners should involve the Fire Service Home Safety Team in attending to those adults who display hoarding behaviours and include this in their risk assessment.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

‘… the third and final agency to be involved raised concerns about ongoing risks from her self-neglect and use of alcohol, and about fire risk’. Fire safety concerns had still not been resolved before her death, meaning that known risks were not effectively managed. Fire was a significant element of the circumstances in which she died.

4. Mental capacity and executive function

In some circumstances there may be cause to consider the mental capacity of an adult who is presenting with hoarding and self-neglect behaviours. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a legal framework for such an assessment to be completed and of next steps to be taken depending on the outcome. The information in this section outlines the necessary considerations and legislation that will apply.

The five statutory principles of the Mental Capacity Act (2005)

- Assume Capacity Unless it is established through assessment the person lacks capacity. You should not assume capacity if the person’s behaviour or circumstances raise doubt as to whether they have the capacity to make the decision.

- Maximise Capacity A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them do so have been taken without success

- Unwise Decisions A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he/ she makes an unwise decision

- Best Interest An act or decision under the act for or on behalf of a person who lacks mental capacity must be undertaken in their best interests

- Least Restrictive Can the purpose be effectively achieved in a way that is least restrictive of the persons rights and freedom (this does not mean that no actions are taken)

Assessing mental capacity

An assessment of mental capacity must be time-specific and decision-specific.

Decision-specific

About a decision which has to be made in relation to a particular matter. An adult may lack mental capacity in one matter but not another.

Time-specific

A person’s capacity to make a decision is only relevant at the point when the decision needs to be made. This is referred to in the legislation as the ‘material time’. Some decisions are one off, for example to pay a bill, and some involve multiple decision points, for example to accept a care provision each time it is offered. People whose mental capacity fluctuates are likely to struggle with this latter type.

The two-stage test of mental capacity

The Mental Capacity Act describes the test for mental capacity in the following way:

s.2(1) ‘… a person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material time he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain’

s.2(2) ‘It does not matter whether the impairment or disturbance is permanent or temporary.’

Stage one – the functional test

Is the person able to:

- understand the information relevant for the decision including the merits of choosing one way or another?

- retain this information?

- use or weigh it and make a decision?

- communicate their decision?

If they are unable to perform one or more of the steps they are functionally unable to make the decision. Stage two involves identifying the likely cause of their difficulty.

Stage two – the impairment test

a) Does the person have an impairment or disturbance of the functioning of the mind or brain? There does need to be some evidence of an impairment or disturbance but not necessarily a formal diagnosis.

It may be temporary or permanent but is present at the point the decision needs to be made.

b) If yes, is this impairment likely to be the cause of the functional difficulty identified in Stage One?

This link between the practical difficulty and a cognitive impairment is known as the ‘causative nexus’.

If yes to a) and b), the person is deemed to lack mental capacity for this decision.

If after all appropriate help and support has been given to the adult and they are still assessed as unable to make a particular decision at that particular time, any action that is taken MUST be informed by the principles of choice, respect and dignity for the adult concerned, with a clear focus at all times on helping them to achieve the outcomes they want. Areas of risk and concerns MUST be discussed and details of the discussion with the adult around risks must be recorded (defensible decision making).

Practitioners MUST always make every effort to establish whether the adult is being unduly influenced or coerced by another person. For example, if you believe they are being coerced, the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court could apply.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

Mental capacity did not receive adequate consideration in several situations involving high risk decision-making, no mental capacity assessments took place, and no attention was paid to the possible loss of executive function. There was an over-reliance on assumptions of mental capacity and on the concept of life-style choice.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Rachel)

Partner agencies held different views regarding Rachel’s mental capacity. Given the level of concern, it would have been good practice for partners to work together to assess Rachel’s mental capacity regarding her care and support needs.

Executive function

Executive functions include planning and organisation, flexibility in thinking, multi-tasking, social behaviour, emotion control and motivation.

Certain disorders of the mind or brain are more widely recognised to be associated with executive dysfunction and include acquired brain injury, dementia, delirium, learning disability, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. However, many other mental disorders can be associated with executive dysfunction including schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and personality disorders. Acute intoxication with drugs or alcohol is also an impairment of the mind or brain.

When executive function is impaired, it can inhibit appropriate decision-making and reduce an adult’s problem-solving abilities. Adults with executive impairment can often present very well in a formal assessment of cognition and mental capacity and articulate with good verbal reasoning skills however they often can “talk the talk but not walk the walk.” Adults with executive impairment are often not aware of any cognitive deficit.

Many of the traits and behaviours observed in executive impairment vary in degree, (they exist on a continuum) and are also observed in the wider population which can make assessment very difficult. Detecting executive impairment and assessing the effect on mental capacity can be very challenging. This can have significant implications because failing to carry out a sufficiently thorough mental capacity assessment in these situations can expose an adult at risk to substantial risks. Speaking with carers, friends who know the adult, and gathering information from any other agencies that the adult may be known to such as housing, environmental and emergency services, may provide clarity of the potential mismatch.

A key to the relationship between executive function problems and a person’s mental capacity is the extent to which they have insight into their practical difficulties. A person who does not understand that in practice they make a decision about what to do but don’t do it, is failing to understand a key piece of ‘relevant information’. They will struggle to consider options for support with their difficulties if they do not recognise what is really happening.

Distinguishing between unwise decision making and decisions affected by executive impairment can also pose a challenge. It is imperative that the assessor uses the functional test, to consider the process of how the adult reached that decision.

Fundamentally, in unwise decision making, the adult is fully aware but consciously disregarding or giving less weight to certain facts relevant to the decision. In executive impairment, the adult cannot access and integrate the correct pieces of information and use them in a meaningful way to make the decision. Repeated assessments help to get a better sense of any repeated mismatch between the adult’s words and actions. Although there is no case that is determinative of this point, Essex Chambers’ guidance states that:

‘You can legitimately conclude that a person lacks capacity to make a decision if they cannot understand or ‘use and weigh’ the fact that they cannot implement in practice what they say in assessment they will do.’

BUT you can only reach such a finding where there is clearly documented evidence of repeated mismatch. It is therefore important that professional curiosity is applied in situations where executive functioning is questioned. This more longitudinal and holistic assessment of mental capacity is essential in detecting the more subtle effects of executive impairment on decision making. However, it is clear that this approach does not sit neatly with the very distinct legal definition of a determination of capacity being decision and time specific, highlighting one of the difficulties with the current legal framework.

Information from this section adapted from the Grab Sheet on MCA Guidance: Executive Functioning produced by Blackburn with Darwen Safeguarding Adults Board, Blackpool Safeguarding Adults Board and Lancashire Safeguarding Adults Board can be found in Appendix 6.

When a care and support needs assessment is completed, executive function should be considered as well as mental capacity. Adults who self-neglect generally have the mental capacity to make related decisions but poor executive function

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR William)

Practitioners need to consider executive function in the context of not just relying on what the adult says, but also what they are able to do. An approach should be wider than simply ‘tell me’ and be informed by ‘show me’. This reinforces the need to consider executive function in a multi-agency context, which in turn promotes an informed understanding of the adult’s right to self-determination versus the duty of care.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Rachel)

Self-neglect was repeatedly identified when Rachel was admitted to hospital and on discharge. Mental capacity assessments were considered however not comprehensively completed to assess Rachel’s executive function to understand why she presented as having mental capacity but was unable to follow through on agreed actions to reduce the risks she was living with.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

There is a difference between the ability to understand and reason through the elements of a decision in abstract discussion, and the ability to use or weigh that relevant information in the moment when the decision needs to be made and enacted.

5. Overview of best practice to support an adult who is self-neglecting

In October 2018, the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) published guidance on working with people who experience self-neglect based on national research. This best practice approach is based on the principles of Making Safeguarding Personal where the adult is fully engaged and consulted throughout and their wishes and views are central to the final outcomes as far as is possible.

Below are some general pointers for an effective approach:

Multi-agency

Engage in effective multi-agency working to ensure inter-disciplinary and specialist perspectives, and coordination of work towards shared goals.

Person centred –Try to ‘find’ the whole person and to understand the meaning of their self-neglect in the context of their life history, rather than just the particular need that might fit into an organisation’s specific role. Respect the views and the perspective of the adult, listen to them and work towards the outcomes they want. Find what motivates them.

Acceptance

Proactive risk management may be the best achievable outcome. Practitioners must work collaboratively with the adult with the aim to minimise risks and meet need.

Analytical

It may be possible to identify underlying causes that help to address the issue.

Non-judgemental

Practitioners must be aware of the impact of their own values and beliefs. It is not helpful for practitioners to make judgements about cleanliness or lifestyle; everyone is different.

Empathy

Practitioners must be aware of the impact of their own values and beliefs. It is not helpful for practitioners to make judgements about cleanliness or lifestyle; everyone is different.

Trust

Take time to build rapport and a relationship of trust, through persistence, patience and continuity of involvement. Short term interventions are not likely to be successful. Providing small practical help at the outset may help build trust.

Trauma-informed

Use strengths based and empowering conversations to explore why the adult is making these decisions rather than focusing only on what they are doing/ not doing. Consider what life experiences may have contributed to this situation. Consider that an adult may feel disempowered and overwhelmed within the system. Provide reassurance and be clear of what support may be available and what will happen next. This builds trustworthiness and felt safety. (See working definition of trauma-informed practice).

Strengths based

See Appendix 8 for a strengths-based assessment tool.

Reassurance

The adult may fear losing control, it is important to allay such fears.

Collaborative working

Collaborate with the adult. Spot moments of motivation that could facilitate change, even if the steps towards it are small. Work together with the adult to agree steps that are aligned with the adult’s wishes and goals. This approach should be respectful of the adult, and their ability to work in terms of pace.

Exploring alternatives and options

Fear of change may be a barrier so explaining that there are alternative ways forward may encourage the adult to engage.

Always go back

It is important to build trust, pivotal in this is being open, transparent, and realistic. Regular, encouraging engagement and gentle persistence may help with progress and risk management.

Be supportive of their carer

Where an adult has the mental capacity to choose not to receive support from agencies, professionals need to appreciate that the Carer still remains a Carer and probably becomes even more isolated when the adult declines support that is being offered.

Practical tasks

- Risk assessment

Have effective, multi-agency approaches to assessing and monitoring risk. Be honest, open and transparent about risks with the adult and explore achievable options together.

- Risk to others

You must consider whether anyone else is at risk as a result of the adult’s self-neglect behaviours. This may include children or other adults with care and support needs. A safeguarding adult concern referral can be made via the Torbay and Devon Safeguarding Adults Partnership website.

- Assess mental capacity

Assessment of mental capacity must be time and decision-specific and consider the adult’s executive functioning as appropriate. Ensure practitioners are competent in applying the Mental Capacity Act (2005) in circumstances of self-neglect.

Decisions assessed could be:

- in relation to accommodation (for example, to remain at home)

- in relation to care and treatment (for example, to refuse care, support or medical treatment)

- keeping safe (for example, to seek help or support).

- Make a plan

Making clear what is going to happen; a weekly visit might be the initial plan

- Mental health assessment

It may, in a minority of circumstances, be appropriate to refer an adult for Mental Health Assessment

- Signpost

To effective sources of support

- Contact family

With the adult’s consent, try to engage family or friends to provide additional support and to gather the views of other people who are important in the adult’s life. If an adult lacks mental capacity, the views and wishes of the adult at risk (and their representatives) should be gathered as part of the best interest decision(s).

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

The family members participating in this review have all raised concerns about the extent to which they were kept informed, consulted and given advice by practitioners. They advise services to ensure there is more consistent and informative involvement with families.

- Carer’s assessments and support

As a general principle, Carers or family members who are supporting an adult who is persistently self-neglecting should be proactively offered support by the agencies that are in touch with the family – this can be simply by asking the Carer what help they need, and doing this routinely e.g. on a monthly basis where the level and frequency of care is very intensive and/or there are signs of carer breakdown and/or deterioration of the adult with care and support needs. They should also be offered a Carer’s assessment in accordance with the Care Act 2014.

Torbay Carers support can be accessed here: Torbay Carers Service – Torbay and South Devon NHS FT

Devon Carers support can be accessed here: For professionals – Devon Carers

- Decluttering and cleaning services

Where an adult cannot face the scale of the task but is willing to make progress, offer to provide practical help. Remember research has shown that decluttering can be deeply upsetting for an adult who self-neglects and this should be done in partnership with them. Link to interests for example environmental concerns – link into recycling initiatives could help to engage the adult.

- Utilise partner agencies

Those who may be able to help include the RSPCA, the fire and rescue service, environmental health, housing and voluntary sector organisations.

- Occupational therapy assessment

Physical limitations that result in self-neglect can be addressed.

- Frequent hospital admissions

Discharge/ transfer plans from hospital/care should be made early, i.e. starting at the time of admission and signs of self-neglect promptly assessed and support provided wherever possible using effective multi-agency discharge planning. Where there are frequent hospital admissions, each admission should not be seen as an isolated incident but the whole history considered. It is essential that before an adult is moved on to another team the situation which has put them at risk must first be stabilised.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Rachel)

The review highlighted the need for partner agencies to have regular multi-disciplinary risk management meetings in high-risk situations where risk assessments are shared so that one joint assessment can be formulated and the level of risk agreed and understood by all partners. This includes in hospital discharge processes to ensure appropriate follow up and review of actions.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

There was an absence of challenge or escalation of concerns during hospital discharge when no effective plan was in place, or when a care package was reduced, or when an adult safeguarding concern was not referred.

- Help with property management and repairs

Adults may benefit from help to arrange much needed maintenance to their home.

- Peer support

Others who self-neglect or who have similar conditions or experiences may be able to assist with advice, understanding and insight.

- Legal literacy

Consider legal options for intervention where required.

- Pre-treatment

This is a phrase often used by psychologists working with adults who have experienced complex trauma. The emphasis is on making the adult feel safe before they feel they can engage in treatment. Pre-treatment includes gradually building up trust between the practitioner and the adult, demonstrating care and empathy rather than focusing on case management, offering choice, empowerment and involving the adult in their care. Where possible connecting the adult with other services or resources such as mindfulness materials, breathing exercises, helping them with grounding techniques and establishing support networks can create a foundation to then move on to treatment options. This could also be thought of in terms of stages of change (see Appendix 4) where an adult is still in a pre-contemplative or contemplative stage.

- Counselling and therapies

Some adults may be helped by counselling or other therapies. Cognitive behaviour therapy, for example, may help adults with obsessive compulsive disorder, hoarding disorder or addictions.

Duty of care

Generally, the law imposes a duty of care on a practitioner in situations where it is ‘reasonably foreseeable’ that the practitioner might cause harm to adults through their actions or omissions. It exists when the practitioner has assumed some sort of responsibility for the adult’s care.

To discharge the legal duty of care, practitioners must act in accordance with the relevant professional standard of care. This is generally assessed as the standard to be expected of an ‘ordinarily competent practitioner’ performing that particular task or role. Failure to discharge the duty to this standard may be regarded as negligence.

If you are concerned that a situation at work (for example, staffing levels or workload) could lead to your duty of care being compromised, then you should raise these concerns with your employer and record your concerns appropriately in line with local policy.

6. Identifying the level of risk or harm to the adult

At all levels

- Use a trauma informed approach and seek to develop a relationship with the adult.

- Seek advice and guidance.

- Complete relevant risk assessments such as falls risk, skin damage, nutritional need etc

- Ensure supervision and support is in place

- Consider if escalation is required

- Consider the safety of other adults and children – ‘Think Family’.

6.1 Responses to low-level risk or harm

What are low risk concerns

Low-level concern is where criteria for further enquires under safeguarding are unlikely to be met. No impact and not reportable. Agencies should keep a written internal record of what happened and what action was taken, following your own internal process. Where there are a number of low-level concerns consideration should be given as to whether a safeguarding concern referral should be raised due to increased risk.

Circumstances could include, but are not exclusive to

- Concern about an adult who is beginning to show signs and symptoms of self-neglect.

- Property neglected but all services/ appliances in working order.

- There is no / low risk or impact to self or others.

- Risks can be managed by current professional oversight or universal services.

- The adult is not at risk of losing their place within the community.

- Some evidence of hoarding – no impact on health/safety.

- No access to support

- Non-concordant with support but no impact on health / safety / wellbeing

Responses to low risk concerns

Where presenting risks of self-neglect have been identified as “low”, the following actions should be considered by the most appropriate practitioner(s).

An up-to-date assessment of the adult’s needs should be obtained where applicable or where none exist, the need for appropriate assessments should be considered. Future monitoring should always consider escalation to higher risk categories and use of safeguarding adult procedures. Information, advice, and signposting should be considered, for example:

- Information / advice about risks and what options there are for reducing risks

- Promoting self-help (asking for help if needed, keeping appointments)

- Information / advice about health or care needs

- Financial information / advice

- Signposting to universal services (e.g., GP, Fire and Rescue Service, Leisure Services, and Libraries) for support as appropriate

- Tenancy support

- Floating support

- Care Act (2014) assessment / re-assessment / review

- Provision of social care services (long-term or short-term Reablement) including direct payment / personal budget

- Health assessment / re-assessment / review

- Health treatment / intervention (including action intervention under the Mental Health Act 1983)

- Fire alarm fitted; sprinkler system fitted

- Change of accommodation. Regular, low-level concerns can amount to a far higher level of concern which may require further enquiries under safeguarding adult procedures. Where you are faced with repeated low-level concerns you may need to consider if this is now high level.

- Ensure your assessment and intervention is trauma informed.

6.2 Responses to significant or very significant harm levels

What are significant or very significant risk or harm levels

Incidents at this level require consultation and should be discussed with your Designated Safeguarding Lead or Safeguarding Adults Service. There is some harm or risk of harm which may include situations where presenting circumstances indicate risk factors are present that place the adult at risk of harm through self-neglect, but available information indicates that risk level may be significant but not considered to be critical. This can include but may not be exclusive to:

- Some signs of disengagement with professionals

- Indication of lack of insight

- Lack of essential amenities or food provision

- Collecting a large number of animals in inappropriate conditions.

- Increasing unsanitary conditions

- There is medium risk and some impact to self or others

- Non-concordance with medication – medium risk to health and wellbeing.

- Property neglected, evidence of hoarding beginning to impact on health and safety

- Where animals in property are impacting on the environment with risk to health

Responses to significant or very significant levels of harm

Torbay and Devon Safeguarding Adults Partnership agree that we start with the presumption that concerns about an adult with care and support needs who may be neglecting themselves are more proportionately addressed through an assessment of their care and support needs (Care Act 2014 assessment) as this will identify the factors resulting in the self-neglect behaviours. An adult safeguarding concern should be considered where assessment and provision has been unable to sufficiently reduce risks.

However, where presenting risks of self-neglect have been identified as very significant, safeguarding adult procedures should be used and a safeguarding adult enquiry should be coordinated subject to the consent (or appropriate over-riding of consent) of the adult at risk.

The adult’s safeguarding enquiry should result in a protection plan being devised which could include any of the actions / interventions described above when responding to a potential significant level of harm. In self-neglect circumstances, the adult’s safeguarding enquiry should include specific consideration of:

- The mental capacity of the adult at risk in relation to specific decisions and their executive functioning, as required;

- Involvement of the adult at risk (and / or their family / a representative), including in the development of a protection plan;

- A review of current arrangements for providing care and support. Does there need to be an assessment / reassessment / review? This should include any Unpaid Carer arrangements;

- Options for encouraging engagement with the adult at risk (e.g. which professional is best placed to successfully engage? Who would the adult respond most positively to?);

- Any legal options available to safeguard the adult. Legal advice should be sought;

- Whether there are any other people at risk (including children) and what action needs to be taken if this is case;

- A contingency plan, should the agreed protection plan be unsuccessful;

- How agencies / professionals will keep in regular communication about any changes or significant events / incidents;

- Support for front-line practitioners working with the adult (e.g. in responding to a refusal of care and support or signposting). As with all safeguarding adult enquiries, it is important that details of actions and decision making are clearly recorded. Where the adult at risk does not consent to the action under safeguarding adult procedures, professionals will need to consider:

- Whether it would be appropriate to override consent; and / or

- Whether the adult has the mental capacity to consent; and / or

- Whether the adult would be accepting of any other support / intervention outside of safeguarding adult procedures (refer to low level interventions)

- Ensure your assessment and intervention is trauma informed.

There are other occasions where an adult safeguarding concern referral about self-neglect should be made, such as when there is a concern that people or organisations who ought to be supporting the adult are failing to do so, or where someone is preventing the adult from accessing the support they need.

6.3 Responses to critical risk or harm level concerns

What are critical risk or harm level concerns

Incidents at this level MUST be reported to your Designated Safeguarding Lead or Line Manager without delay. There is a critical risk of harm. This includes the most serious and challenging presenting circumstances, including but not exclusive to:

- Living in squalid or unsanitary conditions

- There is extensive structural deterioration / damage in the property causing risk to life

- Refusal of health / medical treatment that will have a significant impact on health / wellbeing.

- High level of clutter / hoarding impacting on health and wellbeing, including fire hazard

- Behaviour poses risk to self and others

- Life is in danger without intervention

- Appearance of malnourishment

- The adult is not accepting any support or any plans to improve the situation

Responses to critical risk or harm level concerns:

Where presenting risks of self-neglect have been identified as critical, safeguarding adult procedures should be used and a safeguarding adult enquiry should be coordinated. Attempts should still be made to seek the adult at risk’s consent for the safeguarding adult enquiry to proceed, however where this is not provided consent should be overridden given the seriousness of the concerns. This is so that the concerns can be fully explored on a multi-agency basis and reassurance can be provided that all possible options to manage risk have been attempted.

All safeguarding adult concern referrals should be raised with the relevant Adult Social Care safeguarding adults service in line with safeguarding adult procedures. Safeguarding adult procedures provide a formal, multi-agency framework for sharing information, assessing and managing risk.

When a safeguarding concern has progressed to a s.42(2) safeguarding enquiry, the practitioner responsible for leading the enquiry should ensure that immediate risks are mitigated as part of the risk reduction plan and approach.

In self-neglect circumstances, the safeguarding adult enquiry should include specific consideration of:

- The mental capacity of the adult at risk in line with the principles of the MCA 2005.

- Involvement of the adult at risk (and/or their family/a representative), including in the development of a protection plan.

- A review of current arrangements for providing care and support. Does there need to be a Care Act 2014 assessment/reassessment or review? This should include any Unpaid Carer arrangements.

- Options for encouraging engagement with the adult at risk (e.g. which professional is best – placed to successfully engage? Who would the adult respond most positively to?)

- Any legal options available to safeguard the adult. Legal advice must be sought as required

- Whether there are any other people at risk (including children) and what action needs to be taken if this is case

- A contingency plan, should the agreed risk reduction plan fail

- How partner agencies or professionals will keep in regular communication about any changes or significant events/incidents

- Escalation and notification to senior managers of the adult’s circumstances

- Support for front-line practitioners working with the adult

- Ensure your assessment and intervention is trauma informed

Safeguarding children

The Children Act (1989) is the legislation that underpins child welfare law in England and Wales. Safeguarding children refers to protecting children from maltreatment, preventing the impairment of their health or development and ensuring that they are growing up in circumstances consistent with the provision of safe and effective care. Growing up in a property with environmental concerns, including self-neglect and hoarding concerns, can put a child at risk by affecting their development and in some circumstances, leading to the neglect of a child, which is a safeguarding issue.

The needs of the child at risk must come first and any actions considered and taken must reflect this. Therefore, where children live in the property, a safeguarding concern should be raised immediately with the relevant multi-agency safeguarding hub.

Regarding children in Torbay, you can make a referral to the Torbay Multi-Agency Safeguarding hub

Regarding children in Devon, you can make a referral to the Devon Multi-Agency Safeguarding hub

7. Multi-agency partnership working

Multi-agency partnership working is necessary and especially important in any complex circumstances. Multi-agency working ensures information, risks and concerns are shared and discussed. It is essential that the lead agency is identified at the outset in order to co-ordinate partner agency involvement.

Multi-agency risk management meetings will be crucial for ensuring a collaborative approach to supporting adults who self-neglect. The lead agency will be responsible for arranging and leading multi-agency risk management meetings and ensuring appropriate agency attendance from the beginning.

This should provide a multi-agency response so that an action plan can be formulated and reviewed which will detail multi-agency responsibility. It will also identify and record those situations where there is a reputational risk and provide access into the escalation processes of partner organisations if required.

For further guidance regarding information sharing see the TDSAP Information Sharing protocol.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR June)

The absence of effective multi-agency collaborative practice in response to June’s care and support needs was a major oversight in this case. Whilst there were individual service responses and interventions, there was no coordinated multi-agency action plan designed to address both the scale and urgency of June’s self-neglect. Consequently, no agency was coordinating all elements of risk or had a holistic view of June’s care and support needs.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Rachel)

In complex cases of self-neglect partner agencies should identify and agree a lead practitioner so that that practitioner can co-ordinate information gathered, lead the multi-disciplinary meeting (including discharge meetings) and work with persistence as both an advocate and a single point of contact. This should include involving relevant family/friends and acknowledge the crucial part they play in such a meeting.

Escalation

In situations where there is a concern that an adult’s lifestyle choices or behaviour are likely to result in serious harm, or even death, and current agency involvement has not been effective in managing the risk, partners should refer to the TDSAP Escalation protocol and ensure that this is escalated appropriately to relevant managers within partner organisations so that agreement can be reached regarding next steps.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR William)

Practitioners should ensure they are aware of how to initiate effective multi-agency meetings and must be familiar with internal escalation processes in response to any barriers that arise.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Alec)

A multi-agency meeting will ensure that known information and risks are shared, and facilitate agreement regarding how the circumstances will be monitored and steps to be taken should the situation not improve but deteriorate further. Escalation protocols should be accessed where partner agencies do not support multi agency meetings.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

In some situations it appeared that no service took control of a deteriorating situation, with missed opportunities for joint working, for example on mental capacity or adult safeguarding concerns

8. Undertaking assessments despite capacitated refusal

Lack of engagement or capacitated refusal should not prevent effective risk assessment.

Where an adult declines a needs assessment, Section 11 of the Care Act 2014 provides a legal framework to carry out a needs assessment if the adult is experiencing, or at risk of, abuse or neglect. This can enable a multi-agency assessment of risks and information sharing within a safeguarding response to explore a robust risk management plan and identify any required actions and proportionate next steps.

As a matter of practice, it will always be challenging to carry out an assessment fully where an adult with mental capacity has declined. Practitioners and managers should record all the steps that have been taken to undertake a needs assessment including involving the adult and any Carer, as required by section 9(5) of the Care Act 2014, and assessing the outcomes that the adult wishes to achieve in day to day life and how their needs could be met that may contribute to the achievement of those outcomes, as required by Section 9(4) of the Care Act 2014.

In light of the adult continuing to decline or due to capacitated life-style choices, the result may either be that it has not been possible to undertake an assessment fully or the conclusion of the needs assessment is that the adult declined to accept the provision of any care and support. However, case recording should always be able to demonstrate that all necessary steps have been taken to carry out a needs assessment that are required, reasonable and proportionate in all the circumstances. This should include as appropriate a mental capacity assessment demonstrating that executive functioning has been explored as far as is possible.

As part of the assessment process, it should be demonstrated that appropriate information and advice has been made available to the adult, including information and advice on how to access care and support. In circumstances where an adult has declined an assessment and support and remains at high risk of serious harm as a result, a Section 42(2) safeguarding enquiry should be undertaken.

9. Self-neglect safeguarding enquiries

Section 42 of the Care Act 2014 outlines the legal duties for safeguarding adults:

‘Section 42 Enquiry by local authority

(1) This section applies where a local authority has reasonable cause to suspect that an adult in its area (whether or not ordinarily resident there) –

(a) has needs for care and support (whether or not the authority is meeting any of those needs),

(b) is experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect, and

(c) as a result of those needs is unable to protect himself or herself against the abuse or neglect or the risk of it.

(2) The local authority must make (or cause to be made) whatever enquiries it thinks necessary to enable it to decide whether any action should be taken in the adult’s case (whether under this Part or otherwise) and, if so, what and by whom.’

Section 6 (above) provides guidance on when safeguarding adult concern referrals should be raised. When a safeguarding adult concern referral is raised with the local authority, the local authority will determine if a section 42(2) safeguarding enquiry is required. Section 42(2) safeguarding enquiries may be led by the local authority or ‘caused out’ to partner agencies.

Six Safeguarding Principles[1]

The principles MUST underpin all adult safeguarding work (each principle can have different weight given unique circumstances for each adult dependent on support networks/ ability to protect self/ mental capacity):

- Empowerment: Adults being supported and encouraged to make their own decisions and informed consent

- Prevention: It is better to take action before harm occurs.

- Proportionality: The least intrusive response appropriate to the risk presented.

- Protection: Support and representation for those in greatest need.

- Partnership: Local solutions through partner agencies working in partnership with the adult and their communities. Communities have a part to play in preventing, detecting and reporting neglect and abuse.

- Accountability: Accountability and transparency in safeguarding practice.

Objectives of an enquiry

The objectives of statutory Care Act 2014 s.42(2) safeguarding enquiries are to:

- establish facts

- ascertain the adult’s views and wishes

- assess the needs of the adult for protection, support and redress and how they might be met

- protect from the abuse and neglect, in accordance with the wishes of the adult;

- make decisions as to what follow-up action should be taken with regard to the person or organisation responsible for the abuse or neglect

- enable the adult to achieve resolution and recovery

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

There were shortcomings in actions to safeguard the individuals concerned and evidence that practitioners can become desensitised to extreme living conditions and fail to act. The shortcomings included both a failure to make safeguarding referrals and a failure to pursue safeguarding enquiries in response to referrals made, in some cases on erroneous grounds that indicated a lack of understanding of criteria. Missed opportunities can present when there is a failure to pursue a safeguarding enquiry following repeated referrals about evident self-neglect.

[1] Reference: https://www.scie.org.uk/safeguarding/adults/introduction/six-principles

10. Safeguarding plans

In some circumstances following a safeguarding enquiry relating to concerns of self-neglect, it will be necessary to have a safeguarding plan. This will usually be in circumstances where the risk cannot adequately be managed or monitored through other processes.

Safeguarding plans will not always be required, for example, in circumstances where the risk to the adult can be managed adequately through ongoing assessment and support planning, through Care Programme Approach by Mental Health services, or through a positive risk taking and management plan approach.

In other circumstances, for example, where the adult has been assessed as having mental capacity to make informed decisions about their care and support needs, and has been given all reasonable support and encouragement to accept support to meet those needs, however still chooses to refuse support, it may be agreed that the action required is to provide information and advice including how to make contact in the future so that the adult has this information should they reconsider and change their mind.

However, particularly where the risks to independence and wellbeing are severe (e.g. risk to life or that of others) and cannot adequately be managed or monitored through other processes, it will be necessary to have a safeguarding plan to monitor the risk in conjunction with other agencies. In self-neglect circumstances this would usually involve health service colleagues, but other agencies may well need to retain ongoing oversight and involvement (e.g. environmental health, housing). If the safeguarding plan is still declined and the risks remain high, the meeting should reconvene to discuss next steps. Partner agencies should not end their involvement just because the adult is not accepting the safeguarding plan and legal advice should be sought in these circumstances.

11. Recording

General principles

It is important to record assessment, decision-making and intervention in detail to demonstrate that the required process has been followed and that practitioners and managers have acted reasonably and proportionately. There should be an audit trail of what options were considered and why certain actions were or were not taken. At every step and stage in the process record the situation, what you have considered, who you have collaborated with and what decisions have been reached. This may appear a time-consuming process, however it is necessary to put your activity notes into a framework of considerations and demonstrate why you have chosen a particular course of action.

12. Bringing professional involvement to a close

Practitioners should work collaboratively with the adult to improve outcomes and address in a partnership working approach. This will be based on decisions made with the adult themselves, their families / Carers (if appropriate) and any other partner agencies involved.

There may come a point at which all options have been exhausted, and no improvement has been established. In circumstances where a critical level of harm has been identified and it has not been possible to reduce risks, senior management must be informed and consulted.

Where safeguarding adult procedures have been used, a decision to end involvement must be made on a multi-agency basis and have consideration of whether the risks have sufficiently reduced to justify this decision. The shared decision will be recorded highlighting any monitoring that may be in place. It will also be clear that future concerns will be reassessed if risks are identified as increasing again.

Where safeguarding adult procedures have not been initiated (because the level of risk / harm is deemed to be low or due to a lack of consent) a decision to end involvement should be communicated with the other partner agencies involved.

13. Increasing engagement of the adult with partner agencies

Reasonable adjustments to increase engagement can include:

Accessible information: Ensure that you have explored if the adult has any specific communication needs and protected characteristics that require a specific and sensitive approach that demonstrates inclusion of these needs. You should take steps to ensure that the adult receives information that they can access and understand. Consider appropriate advocacy and interpreter services.

Method of contact: Is a phone call, text reminder, email or letter more appropriate or accessible? Does the appointment need to be arranged in the adult’s first language (with professional interpreter – do not use family members or friends), do they need information in brail or through a support worker/carer? If the adult has a hearing impairment, do they need a professional sign interpreter or a lip speaker? Do they prefer written information? Would text reminders help? Does the adult have access to a text phone?

Location of the visit / appointment: Where could the appointment best be provided? (Could transport be arranged or is a home visit more appropriate?)

Appropriate time of day: Some adults may function better or be able to get out of the house and make decisions later in the day. Consider whether medication may impact on the adult at certain times of the day.

Other coinciding appointments or the need to coordinate appointments (for example, if an adult requires blood tests and needs an appointment with the practice nurse or GP, could all of these services be arranged for one visit reducing the need for multiple visits).

Memory issues: Can reminders for appointments be provided? Consider technology enabled care services (TECS)

Gender of the professional: For example, there may be a history of trauma, cultural needs or other reasons why an adult would struggle to engage with a male/female practitioner.

If the adult has a carer: Flexibility to plan around the carer’s availability should be considered for appointment timing. The carer may also face barriers to accessing care and support and if this is known, then both adults will require assistance and potentially multi-disciplinary referrals. Carer’s should be offered a referral to the relevant carers service including assessment under section 10 of the Care Act 2014. See ‘Carers assessment and support’ in Section 5 above.

The offer of support and/or referrals should be revisited at regular intervals; it may take time for someone to be ready to accept support.

Offer choices where possible to empower the adult and help them to feel in control.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Rachel)

It is imperative that practitioners recognise specific individual needs and adapt their approach accordingly rather than a ‘one size fits all approach’ which does not promote professional curiosity. Engagement can be variable and impacted by mental health, use of alcohol and other factors which affected her engagement with partners at various stages.

Practitioners should ensure they apply appropriate strategies to promote more successful engagement outcomes.

(See also Appendix 10 ‘Principles of engagement to improve communicating and working with adults’)

14. Carers

With the adult’s consent it can be helpful to engage and provide support with the adult’s family or unpaid carers. Where an adult lacks mental capacity to make specific decisions regarding their welfare it is necessary to clarify whether anyone with decision making powers have been appointed i.e. a Lasting Power of Attorney, or whether steps need to be taken to ensure appropriate representation.

Carers have the same rights as people with care and support needs under the Care Act 2014. In circumstances where a carer is supporting someone who self-neglects or presents with hoarding behaviours or indeed lives with the person, then statutory requirements may apply.

Carers assessments must seek to establish the carer‘s need for support (practical and emotional), and the sustainability of the caring role itself. The local authority must include a consideration of the carer’s potential future needs for care and support.

Families and unpaid carers can often make a very valuable contribution especially in terms of history of behaviour and what is ‘normal’ for the adult. They may be supportive in establishing a trust relationship between professionals and the adult.

Engaging family members or unpaid carers – the family member or carer of an adult at risk should be engaged wherever possible when the adult at risk has provided consent. This will include being part of planning, decision making and whether they are willing and able to provide support.

In a situation where a carer may contribute to the potential risk to the adult, the suitability to support and/or represent the adult should be considered.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Tony)

It is vital when undertaking an assessment to consider the impact of the circumstances on the Carer. Practitioners must always offer a Carer’s assessment as per the Care Act (2014) requirements. Furthermore, offer advice and signposting regarding any other carer support services that are available.

15. Advocacy

An advocate can:

- listen to the adult’s views and concerns

- help them explore their options and rights

- provide information to help them make informed decisions

- help them contact relevant people

- accompany them and support them in meetings or appointments

Appendix 7 provides an overview of the various types of statutory advocacy.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

Best evidence advocates the use of advocacy where this might assist a person to engage with assessments, service provision and treatment.

16. Hoarding behaviours

In circumstances where concerns specifically relate to hoarding behaviours and associated risks, please see ‘TDSAP Guidance to support partnership working with adults who present with hoarding behaviours’

Learning from case law

A local authority made an application for an order for AC, a 92-year-old, to be moved from her home, where she lived with her son GC, due to hoarding issues and where both of them lacked mental capacity in certain areas. The judge ruled that AC should return to her own home as whilst it was not without risk, it was in her best interests. This ruling shows the importance of upholding human rights wherever possible. See England and Wales Court of Protection Decisions: AC and GC.

17. Supervision and support

Supporting compassionate leadership across partner agencies should be core to professional practice. We understand that working with the complexity of adults who present with self-neglect and hoarding behaviours can create feelings of vicarious trauma to practitioners involved. Support should be available from line managers through supervision and each partner agency’s wellbeing services.

Professional supervision supports practitioners to make sound and effective judgements for the adults that they support. It enables practitioners to reflect on and improve their knowledge, confidence and competence in their practice and to support positive meaningful outcomes for the adult (See Appendix 2).

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (Thematic SAR Self-Neglect)

Supervision was seen as essential to challenge any normalisation of risk and to explore supportively but critically how practitioners were viewing and responding to what they saw.

Learning from TDSAP Reviews (SAR Rachel)

The review highlighted that several partner agencies ceased involvement with Rachel without sufficient rigor and reflective supervision to consider the potential implications of such decisions.

Acknowledgement

With thanks to Manchester Safeguarding Partnership whose guidance has been adapted to produce this guidance for Torbay and Devon safeguarding adults partners.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Legal interventions

Appendix 1 Legal interventions

Appendix 2 A tool for case supervision

Appendix 2 A tool for case supervision

Appendix 3 Resources

Appendix 4 The cycle of change

Appendix 4 The Cycle of Change

Appendix 5 Obesity and self-neglect

Appendix 5 Obesity and self-neglect

Appendix 6 Executive functioning

Appendix 6 Executive functioning

Appendix 7 Statutory advocacy

Appendix 8 Strengths based assessment tool

Appendix 8 Strengths based assessment tool

Appendix 9 Working with adults who are substance dependent

Appendix 9 Working with adults who are substance dependent

Appendix 10 Principles of engagement

Appendix 10 Principles of engagement

Appendix 11 Have you thought about professional curiosity?

Appendix 11 Have you thought about professional curiosity?