Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Safeguarding Adults Review (SAR) referrals with concerns about failure of agencies to work together were received by Torbay and Devon Safeguarding Adults Partnership (TDSAP), for three men who died during the pandemic in the Devon area. A thematic review model was agreed to identify and share learning to improve future interagency practice and prevent deaths or serious harm in similar circumstances.

1.2 The men were aged 59, 53, and 46 years. Whilst the three men had different individual circumstances, there were parallel themes. Their mental health and associated difficulties were complex, with escalating distress and requests for help.

2. SAR process and methodology

2.1 This review was a statutory learning-focused process. The aim was not to re-investigate, but to evaluate and explain professional practice, highlighting challenges, system problems and constraints to practitioner efforts to safeguard adults. Interagency working, and insight into improving responses to men in similar situations are encompassed within the analysis and findings. Case detail required exploration to understand the circumstances and consider potential themes. The Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCiE) Safeguarding Adults Review[1] Quality Markers (QMs)[2] were used in this review as evidence of SAR governance and to demonstrate transparency. See Appendix 6

| Empowerment | Understanding how individuals or representatives were involved in their care.

|

| Prevention | The learning will be used to consider how practice can be developed to prevent future harm to others. |

| Proportionality | The learning from three cases will be more effective in considering systems and if themes are repeated in other cases. |

| Protection | The learning will be used to protect others from harm. |

| Partnership | Partners will cooperate with the review considering how partners are working together to safeguard adults. |

| Accountability | Agencies will be transparent in the review with the TDSAP holding individual agencies to account for agreed recommendations. |

2.2 The Department of Health’s (DoH) six principles for adult safeguarding are included in this review as described below. These are principles that should be applied across all safeguarding activity[3].

2.3 The Terms of Reference were drawn up and confirmed in June 2022, see Appendix 1. The areas centre on the wider context of working with individuals with complex mental health needs, self-harm, and consideration of services from the perspective of trauma informed. The structure of the report is divided into the domains used in the analysis of SARs 2017 – 2019.[4] 1. Direct work with individual(s), 2. Inter-professional and Interagency collaboration, 3. Organisational features of the agencies involved affecting how practitioners and teams worked, 4. SAB leadership, oversight, and governance.

2.4 Decisions were made by TDSAP in conjunction with the Lead Reviewer (LR) about the wider contextual factors, the need to find the right balanced approach, and one that included proportional methodological rigor. There was acknowledgment this review was delayed. Factors impacting on the timeliness of this SAR were highlighted as the pandemic, agency capacity and delay finding an independent LR with the right background and experience. See Appendix 8 for the LR’s biography.

2.5 Agencies provided their internal Management Reviews (IMRs), and from these a multi-agency chronology of events for each man was produced. The chronologies generated key events (KE) and questions, see footnotes in chronologies Appendix 2,3, and 4. These identified that supplementary information was needed to clarify facts, and explore questions. Unfortunately, there were obstacles in gaining more information.

2.6 There were parallel processes for coroner inquests, held in June and July 2021 and January 2023. The coroner witness statements for all three deaths were provided to the SAR. Mental health policies and operating procedures were provided in November and late December 2022. The LR also spoke with the coroner and attended an inquest via video in January 2023.

2.7 As a result of the difficulties experienced, the planned collaborative systems model with relevant staff was not possible, therefore, to compensate, a blended review model[5] was used. This included a combination of IMRs, and interviews with available relevant staff and family members, see Appendix 7. Perspectives of individuals, families and organisations were included from IMRs, and inquest witness statements. The latter was also used to offset the inability to access additional information.

2.8 Relatives of one man did not want involvement, and friends of another could not be located. The third man’s family did not want to engage with the review, and in a telephone discussion, requested an opportunity to consider findings after the inquest. Late in the process the LR identified another relative. A TDSAP representative made enquiries ensuring there was an opportunity for all relevant family to be involved. The next of kin of one man who participated in the review, raised other matters, requesting answers to broader questions about the mental health care. Disappointingly it was not possible to address these in this review due to the inability of mental health services to provide additional information. These questions will now be addressed in a meeting with the family and the relevant clinical team.

2.9 The analysis, findings and themes identified in this SAR will be taken forward by TDSAP and shared with family and agencies involved.

[1] Section 44 (1-3), Care Action 2014

[2] SCiE Safeguarding Adults Review Quality Markers. Comprehensive checklist tool March 2022 – https://www.scie.org.uk/files/safeguarding/adults/reviews/quality-markers/scie-sar-quality-markers-comprehensive-checklist.pdf

[3] Department of Health (2016 Care and Support Statutory Guidance Issues under the Care Act 2014)

[4] Local Government Association ‘Analysis of Safeguarding Adults Reviews (SARs April 2017 – March 2019). https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/National%20SAR%20Analysis%20Final%20Report%20WEB.pdf

[5] from the Torbay and Devon Safeguarding Adults Partnership SAR decision and methodology tree.

3. The men – circumstances of death and personal histories

3.1 The deaths included in this thematic SAR are as follows,

NB, there was limited information available for Adult N, available to this SAR.

3.2 ADULT C

Adult C, aged 59 and white British, died on 4th September 2020. The inquest was held in July 2021. The medical cause of death has been ascertained as multiple injuries due to a fall from height and the Inquest recorded an outcome of suicide, “that it is more likely than not that C intended to take his own life that day”. Adult C jumped from cliffs in Devon, at 18:50pm. At the time he was separated, unemployed, experiencing mental health difficulties and living in supported accommodation. Police received a call from care staff at 13:57, reporting that he had again left the accommodation, there were concerns about mental health and wellbeing. Police began a search and later Adult C was seen, he had fallen halfway down the cliff. A suicide note and a bag containing possessions were found at the top of the cliff. Despite efforts by a lifeboat crew to verbally engage with him, Adult C made his way further to a steeper area and then dropped from the cliff approximately 150 feet sustaining fatal injuries.

3.3 ADULT N

Adult N, aged 53, and white British, died on 11th September 2020. The inquest was held in January 2023. The autopsy recorded a cause of death as asphyxia due to hanging. At the inquest the coroner recorded a narrative conclusion, “at the time of death Adult N was experiencing mental health difficulties……He died as a consequence of his own actions. There was insufficient evidence to conclude this was a planned deliberate act as it was not clear what his intentions were”. The coroner commented that it was possible Adult N was unaware how quickly he would experience difficulty. Prior to death Adult N had a decline in his mental health with multiple ambulance attendances over a five-week period for impulsive overdoses while under the influence of alcohol. Referrals were made to the liaison psychiatry team at the Emergency Department (ED). On the morning of death sometime before 06.00 hrs, he woke his mother asking her if she would like a cup of tea. After about thirty minutes later his mother saw he was suspended, hanging from a banister spindle by a dressing gown cord around his neck. His mother called 999. On the paramedic’s arrival there was no respiratory effort and no cardiac output. Police were contacted and attended, his room was checked and two large 2-litre bottles of cider, one empty and the other three quarters empty, were found. The post-mortem established that Adult N was not intoxicated at the time of his death, nor had he taken any drug in high dosage.

3.4 ADULT B

Adult B, aged 46 and white British, died on 19th January 2021. The inquest was held in July 2021 and the outcome was recorded as suicide; and on the balance of probability, it was an action he intended…“it appears that B jumped off the roof terrace of the building in which he lived. There was nothing to suggest anyone else was involved in his death. It is likely that the fall from this height caused him to become unconscious and he came to rest in a position where breathing was not possible, a set of situations known as positional asphyxia. In the absence of other findings, it is reasonable to attribute death to this”. Adult B is described as having a number of mental health diagnosis and a mild to moderate learning disability or difficulty. Adult B was described as mentally unwell and distressed prior to death. Staff at the accommodation last saw him the previous evening. On the morning of 19th January 2021, staff went to his flat and found him missing. Adult B had left shoes and clothes on the floor; his mobile was also found, all which staff thought was unusual, and he was reported missing to police. Following a search of the building he was located at 09:25 am on the ground at the rear of the building. Staff commenced resuscitation attempts but this was not successful, and Adult B was pronounced dead by the ambulance crew shortly after.

4. Adult C background information – pen picture of adult C

4.1 This information is provided with the kind assistance from Adult C’s eldest daughter. Loving memories of her father were shared with this review so the LR and those reading this report could know how he was as a man and a father, when he was well, allowing Adult C to be held at the centre of this themed review.

4.2 Adult C was a much-loved father to three children, as well as stepfather to three from his third marriage, and was a new grandfather to one. Adult C and his eldest daughter shared the same birthday and there was a special bond. The dad his children will always remember was awkwardly funny, extremely caring, and easy to wind up. He was calm, evenly tempered, and super organised. He was a fantastic father. He was especially skilled at DIY and kept the family home in top shape. He enjoyed mowing the grass and was proud of his garden. He was a keen driver and throughout his life drove a range of cars, buses, quadbikes, lorries, and tractors. He loved animals, and although he protested, he enjoyed looking after the many family pets, including hamsters, guinea pigs, rabbits, and cats.

4.3 For much of his adult life Adult C lived in the Southwest, although he grew up in Buckinghamshire. He was born in Chorley Wood and was the youngest child to his parents, and a brother to his sister. After leaving school, which is where he met the mother of his three children, he worked on various farms, mainly as a tractor driver. He loved working in the fields and being on the land. After working in agriculture in his early career he then worked for a local bus company driving school buses, he especially enjoyed taking children on school trips. The family then moved to Devon, after making the decision to move following a family holiday to the seaside, and he worked for many years for Southwest Water in their treatment plant. Here he worked shifts, but this did mean that he enjoyed 11 days on and 11 days off, which he could spend with the family. His family reflect on many happy memories spent during the school summer holidays at the beach, they had a beach hut and would spend long days splashing in and out of the water, he would pull the children along in rubber rings. He always joined in with games and made them laugh a lot. He worked hard to take them on family holidays and was a professional at packing the car without even a centimetre to spare. Once settled in Devon he maintained his friendships in Buckinghamshire with two families, who became honorary Aunties and Uncles to his children. One family even moved to joined them in Devon and moved across the road. He would enjoy many an evening BBQing and cooking up a feast for his friends and family. He collected Toby Jugs and stamps, meticulously organising them.

4.4 Later on in his working life he went on to work as a delivery driver, he volunteered in a British Heart Foundation charity shop and began training to become a driving instructor, unfortunately his mental health meant that he didn’t ever finish that qualification. When his health was good, he was a keen runner, especially enjoying jogging along the seafront. He also played table tennis and joined a local club. He loved the band Queen and would listen to them; he took his daughter to a Queen tribute band for her eighteenth birthday, which to this day is one of her fondest memories of her father. He also loved action type films, especially James Bond and he supported Arsenal Football Club. When his children were growing up, he got hooked on playing Crash Bandicoot (a game he bought for them) on the PlayStation and was even caught playing it when they had gone to bed.

4.5 Adult C suffered with his mental health for nearly 20 years prior to his death. During this time, he suffered peaks and troughs, although even in his better times he never returned to the man he once was. When mentally more stable he was able to rebuild his life, doing voluntary work and gaining employment. In the periods of more stability, he made new relationships and married twice more, although his levels of anxiety and fear impacted on relationships with all family members and friends. Despite at times being very unwell, his family was always at the forefront of his mind and never stopped being his priority. Adult C was 59 years old and three days short of his 60th birthday at the time of his death.

4.6 Social circumstances

Adult C was married three times, most recently in May 2018, and separated in August 2019. Adult C had limited contact with his three adult children, although had telephone calls with his eldest daughter. Supported accommodation with care staff was agreed in the spring of 2020, and he moved into a five bedroomed house with four other residents.

4.7 Employment

Adult C worked in a variety of jobs, in agricultural work, and for Southwest Water and more recently as a logistics delivery driver and appliance installer. Due to the deterioration in his mental health, he had not been employed for some time.

4.8 Care and Support needs

Adult C had a range of care and support needs, these are described as health, mental health, and adult social care needs. The latter included supported accommodation (also known as extra care housing), additional enabling one to one hours on top of core hours at the accommodation for leisure and occupation, prompting of activities of daily living, review, and monitoring of medication for mental health and support to help him minimise harmful alcohol consumption.

4.9 Physical health history

Adult C had physical health care for back pain and a brain scan in 2017. The scan showed evidence of a stroke. A repeat scan in May 2020 showed some evidence of the earlier stroke, but there was no significant change from the 2017 scan. Adult C had a history of excess alcohol use and oesophagitis. In November 2019, he was an inpatient in the District General Hospital (DGH) where he received care for physical health problems related to alcohol detoxification.

4.10 Mental Health history

Between 2001 to 2004, Adult C had at least seven admissions to an acute adult mental health inpatient unit after deterioration of his mental state and suicidal thoughts with intent, i.e., going to the cliffs, constructing a noose in the loft and acts of self-harm. The admissions were both formal under the Mental Health Act (MHA) and informal. His diagnosis was treatment resistant depression, and his presentation was described as complex. Adult C had a course of Electro Convulsive Therapy[6] (ECT) for agitated depression in 2005. During this period his first marriage broke down. Adult C also had long term psychotherapy, family and drama therapy. The psychotherapy was aimed at changing the way he thought and behaved to improve his mental and emotional wellbeing. Family reported that he recovered well. Clinicians noted that Adult C had difficulty in thinking about his problems and behaviours from a psychological perspective and engaging with therapy, and he also struggled to consistently take medication. There was no contact with mental health services after 2005 until April 2017, when Adult C experienced low mood and agitation. The contributory factors included employment worries, an injury resulting in back pain, and sleep disturbance. Adult C declined medication for pain and the GP referred him to mental health services.

4.11 During 2017 there was a significant deterioration in his mental health, and he received daily care from the Crisis Resolution Home Treatment team (CRHTT). Significant events included his pacing around the home all night, he was described as if someone had switched the off button on his brain and he wasn’t there anymore, and it was weeks before he calmed down. His partner found this frightening. A range of medication was tried but he was reluctant to take this. Staff who knew Adult C from earlier mental health care, noted his presentation was similar to previous hospital admissions. Severe depression and anxiety were diagnosed and after discharge from CRHTT, he received support from the community mental health team (CMHT), with a care coordinator, firstly with home visits and later he attended at the office base. Care included medication, talking and self-help books. Adult C repeatedly asked to be admitted to hospital to ‘fix him’. A range of medication was tried, and as soon as one was working, he believed this was not the one for him, and every time medication changed the suicidal thoughts started again. In October 2017, Adult C’s mental health deteriorated again, and he was referred to the CRHTT with depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts. He was refusing medication and found with a belt around his neck pulled tight, he said he wanted to kill himself, after this Adult C was admitted to an older person’s ward. It was noted that each time medication was started, he would feel better, but could not accept he was suffering from anxiety and depression, and he stopped taking medication. When discharged he was prescribed antidepressant and antipsychotic medication. A brain scan was agreed to try and provide some reassurance that there was nothing wrong with his brain, which was a feature of his anxieties. From November 2017 – November 2018, Adult C was supported by the CMHT and discharged when he was doing well. After discharge Adult C wanted to change his medication. This pattern of distress continued over the next two years.

4.12 Since November 2018 Adult C’s distress continued, with his partner as his full-time carer. Adult C was encouraged to attend activities during the day, he attended for a while and then refused. He was described as starting the day in panic, so he kept busy, which took his mind off his illness, and the next day it started all over again and he was not able to deal with everyday life. In December 2018 the GP referred Adult C to mental health services with low mood, anxiety, and an inability to cope. Nothing had changed in two years and Adult C needed more support, CHRTT then provided care. In July 2019 the carer arrangements broke down, he was too dependent and described as childlike. Adult C then stayed with his eldest daughter for a few days. His anxiety was described as ‘through the roof’, and he was constantly pacing. He repeated phrases, that his mind was not working, and that he was broken continuously. His daughter was worried about leaving him alone for fear of what he might do. When he returned home in August 2019, his relationship was over. CRHTT provided support, and respite accommodation with care staff was arranged for a few weeks. Adult C continued his refusal to cooperate with mental health care and treatment. He was then re-referred to community mental health services by his GP with low mood and memory problems, and he was taken onto the caseload of the local CMHT. Later visits to his daughter to meet his new grandchild in 2019 saw Adult C’s behaviour as centred around his anxieties, he was acutely unwell with anxiety and agitation.

4.13 Forensic history / Police involvement

Adult C was known to police due to concerns about his mental health, he did not have any convictions, recorded cautions, or warnings. From October 2019 until death, police had eleven contacts with Adult C in connection with his mental health crisis, suicidal thoughts, threats to jump from the cliffs, threats to harm himself with a knife, and as a high-risk missing person.

4.14 Agencies involved

The agencies involved in Adult C’s care were GP services, mental Health Service, Mental health social worker, Respite supported living, Enabling Support, accommodation with supported Living, Police, and the ambulance service.

[6] ECT is a treatment that involves sending an electric current through your brain, causing a brief surge of electrical activity within your brain (also known as a seizure). The aim of the treatment is to relieve the symptoms of some mental health problems.is an effective treatment most commonly used for severe depression that hasn’t responded to other treatments. It is usually considered when other treatment options, such as psychotherapy or medication, have not been successful or when someone is very unwell and needs urgent treatment.

5. Adult N background information – pen picture

Biographical information available to the SAR for Adult N from all agencies was limited. Adult N was a 53-year-old man who lived with his mother for whom he was the main carer. Adult N had supportive neighbours and felt able to knock on their door seeking support for anxiety a few weeks prior to his death. The neighbour is described as a good friend to the family, and a lifelong friend from his schooldays. Adult N’s father passed away in 2002. He was described by his mother as a kind and even-tempered man, and both got on well with each other.

5.1 Adult N was described as very good at looking after his mother. His mother was concerned about his drinking, and she tried to stop it, as she controlled most of the household budget. His mother explained he would ask for money, and if this was not forth coming, he would threaten to ask family, friends, or neighbours. His mother would have felt very embarrassed about this, so she gave him the funds.

5.2 Social circumstances

Adult N was described as not particularly academic at school. He married around 2003 and went to live in Newton Abbot with his wife, but sadly the marriage only lasted a few years before they separated, although they were married for sixteen years. There were no children and Adult N later moved back to the family home with his mother. His wife continues to live in the same county, and details of their relationship at the time of death is not known. He was in receipt of Employment Support Allowance (ESA),[7] due to struggling with his mental health. In the weeks prior to his death, he described anxieties and worries related to his mother and the pandemic.

5.3 Employment

After Adult N left secondary school, he began working with his father who was an electrician with a local firm. He was taken on full time by the company and then later moved on to another business in the same line of work. Adult N then changed his employment and started working at a local business unit cooking food. After this he went on to become a carer at a care home, mainly working the nightshift, for four or five years. Unfortunately, poor attendance due to sickness led to the end of this employment. Adult N had not worked for thirteen years, his last employment was in a mental health provider as a health care assistant. There are no details as to whether Adult N received the ESA benefit on the criteria of unable to work or, that he was able to work and in receipt of help to return to work.

5.4 Care and Support needs

Adult N’s care and support needs were described as mental health, anxiety, and depression, which was impacted by excess alcohol. The GP prescribed medication for anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Adult N used self-care techniques and general lifestyle changes with the aim of managing symptoms of anxiety and depression, and to prevent deterioration.

5.5 Physical health history

In 2019 the GP was consulted about lower back pain with advice for self-referral to the NHS physiotherapy team and advice given for exercise and lifestyle. There was no other information of note related to physical health history.

5.6 Mental Health history

Adult N was very close to his grandmother who lived with them, and he was very upset when she passed away in the late 1980’s. His mother believed this may have been a trigger for a deterioration in his mental health, as he suffered a breakdown which resulted in treatment at a mental health Unit in Torquay. There was a long history of mental health problems. He was initially diagnosed with severe anxiety and a possible psychotic episode in 1993 where he was admitted to hospital. He had been working in a nursing home at this point, was very stressed at work and he went through a marital breakdown. The GP records show that Adult N had a further episode of anxiety where he required psychiatric input in 2008 and he accessed talking therapies. There was a further episode of depression and there were referrals for talking therapies in 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2017. In August 2020 his GP again referred him to depression and anxiety services.

5.7 In December 2017 Adult N was taken to the ED at the General Hospital after a fall. Here he disclosed a history of depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, with some obsessional thinking which he saw as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)[8]. Adult N disclosed he was drinking daily (two bottles of wine and some whiskey) to ‘block out’ negative thoughts, this was described by him as ‘on and off. Adult N described difficulty sleeping and an inability to gain pleasure from his usual activities such as music and gardening. His mother recalled Adult N had episodes where he went to neighbours houses uninvited to see how they were, or introduced himself as if they weren’t known to them. On occasion he would take his mother along, who felt she should go with him so she could explain and make sure he didn’t say anything untoward or upset people. It seemed at times, he felt he needed over extended contact to make a connection with people, and this could be uncomfortable for the neighbours. Adult N made excuses to check unnecessary small details again and again with people if they were going out or if they were doing a favour for him.

5.8 Since the pandemic lockdown, Adult Ns mental wellbeing deteriorated. He began to drink an excessive amount and was buying two litre bottles of cider from the nearby store. Sometimes this might be two to four bottles a day and he drank them downstairs in the kitchen, but also would have cider in his bedroom. In addition, shortly before his death, he disclosed drinking larger quantities of alcohol (9 litres of cider) each day, starting when he got up in the morning. Adult N was described as never appearing to be physically drunk, in the sense of losing his ability to function, so it was difficult to know exactly how much he had consumed. The neighbour recalled that he sometimes appeared a bit confused when they talked and seemed more anxious recently.

5.9 Agencies involved

The agencies involved in Adult Ns care were the Emergency Department at local general hospital, mental health services – First Response Service (FRS) and Liaison psychiatry (LP), locally commissioned talking therapies, GP, Drug and alcohol service, and the ambulance service.

5.10 Forensic history / Police involvement

None known.

[7] ESA – Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) is type of benefit. It is to help those who are affected by a health condition or disability. Furthermore, their condition must make them less or not able to work. When earning this benefit, people may get one of two things. First, if unable to work person will receive money to cover living costs. Second, you if able to work. Then, person will be provided with help to aid them in working again.

[8] Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental and behavioural disorder in which an individual has intrusive thoughts (an obsession) and feels the need to perform certain routines (compulsions) repeatedly to relieve the distress caused by the obsession, to the extent where it impairs general function.

6. Adult B background information – pen picture of adult B

Adult B is described by the adult social worker, supported living staff and those who knew him as a considerate and kind man, who needed time to build relationships and time to communicate, and that he was often very distressed by intrusive thoughts. Adult B was also described as being protective of others and staff regarding his intrusive sexualised thoughts. This was illustrated by his looking away from and raising his voice at children when they visited the accommodation for Christmas carols. This was perceived as being a way of making sure the children did not have contact with him. Trust was a key contributory factor to whether Adult B would confide or share his thoughts, this was also believed to be a self-protective factor, for example, his concern about being judged by others or embarrassed by his thoughts. As his mental health deteriorated, he was observed to have difficulty in focusing on anything other than his thoughts and feelings, although he continued to engage with those supporting him, but in a minimal way. Adult B was also described as using self-isolation as a way of protecting himself and others due to his thoughts.

6.1 Biographical information available to the SAR for Adult B from all agencies was limited. It is recorded by various agencies that Adult B lived in Devon as a child, and both his parents were deceased. Adult B had a younger sister, from whom he was estranged, with no contact for over thirty years. His sister’s only contact was after death, where she helped the adult social worker clear the flat of personal belongings.

6.2 Adult B described his childhood as ‘not good’; he had difficult relationships with his parents, he described this as mainly related to his having learning difficulties and that his sister did not. Adult B disclosed he was physically abused by both his parents. He disclosed in addition to the physical abuse, he was also sexually abused by his father, a headmaster, and another pupil. Adult B also reported being bullied by others whilst at school. His age at the time of these allegations was not recorded. Police records include details of the emotional and physical abuse by his mother. This was described as his mother frequently hitting him with a rolling pin to the head and with her purse across his face. Adult B disclosed when distressed by intrusive thoughts, that he had sexually abused another young person when he was in his teens. Adult B left home when he was a teenager and presented himself to local services where he was placed into care. Adult B was given a place at a care home in Torquay, and he lived there from approximately 1993 to 2015. Subsequently in 2015 the manager, who had been a friend and carer to B for nearly 20 years moved, and B went with her to other accommodation in Torquay. It is not clear from records if this address was a care home, an adult placement or living with a friend.

6.3 Adult B attended school in Exeter which provided education and support to boys with emotional and behavioural difficulties.

6.4 The police were aware of the allegations of abuse Adult B had made against the headmaster but were unable to progress it any further due to a lack of corroborative evidence needed to bring a prosecution.

6.5 Social circumstances

Adult B had lived in care since he was a young person, and for the last twenty-two years with the same carer until 2018, when B was supported by an adult social worker (Torbay) to move. It is not clear what led to the breakdown of the care arrangements. The long-term carer only visited Adult B once after he moved into his new home, then there was no further contact, which he found distressing. Since May 2018, Adult B lived in extra care housing with care from supported living staff. The accommodation consisted of 29 one-bedroom flats and 16 two-bedroom flats with communal facilities for people normally over the age of 55 years with physical disabilities, mental health needs, older age, and dementia. Each apartment had a small kitchen, the local shop delivered groceries to the building in the morning, and there was also a restaurant providing breakfast and lunch. Staff were available and visited Adult B regularly as and when required throughout the day.

6.7 Employment

There was no detail about previous employment prior to the move to supported living. Since the move Adult B worked as a volunteer on a Monday and a Thursday at a charity shop in Torquay. He stopped volunteering when the shop closed during the pandemic. Adult B said he enjoyed working as a volunteer for the charity, recycling unwanted furniture to those in need. Adult B stated this gave him purpose.

6.8 Physical health history

Adult B was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes many years ago (date not recorded) and had diabetic retinopathy in both eyes which can cause blindness if left untreated. None of the information provided records the extent to which B’s eyesight was affected by this. In 2016, Adult B was diagnosed with hydronephrosis, which is a swelling of the kidney caused by a blockage in the urinary tract and he received treatment. In August 2019, B was admitted to the intensive care unit of the local DGH with a gastrointestinal bleed due to a duodenal ulcer. This was treated successfully. Alcohol use was disclosed by B in 2019 and a factor in this health condition. Adult B was on the GP learning disability register and had annual health checks at the surgery.

6.9 Care and Support needs

Adult B had long term mental health and care and support needs[9]. Adult B had mild learning difficulties which was also referred to as mild learning disabilities in information provided to the SAR. The adult social worker who knew him well described Adult B’s mental health was characterised by psychosis, obsessive thoughts and behaviour and low motivation. In October 2017 the care act assessment recorded his needs as requiring help with nutrition, personal hygiene, being appropriately clothed, maintaining his home, developing / maintaining family or personal relationships, accessing / engaging in work, and making use of community facilities. There was daily support in working hours from supported living staff at the accommodation with one member of staff on duty overnight.

6.10 Mental Health history

In 2008, Adult B was assessed by a learning disability clinical psychologist working within local adult mental health services in Devon.[10] The assessment concluded that Adult B was not eligible for an ongoing learning disability (LD) service due to the low level of impairment. This assessment outlined the view that his predominant need was mental health. Adult B’s first known contact with local adult mental health services was in October 2011 when he was given a differential diagnosis[11] of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), mild learning disability, anxiety, mixed obsessive thoughts, and acts. Records also included developmental disorder – scholastic skills, which was unspecified, and paranoid schizophrenia.

6.11 Adult B is described as receiving a low level of support much like a befriending service rather than treatment from the CMHT until January 2016, when his mental health was recorded as stable, and his care was transferred back to his GP who was provided with medication advice.

6.12 In October 2017, Adult B was re-referred to local mental health services in Devon by his carer and her partner. There was a concern that Adult B’s mental health was deteriorating. Mental Health services recorded that the referral appeared to be a breakdown between Adult B and his carers rather than a specific mental health issue. It was concluded that he was not presenting with any acute mental health concerns or risks to himself or others. Between November 2017 and August 2019 there was no further contact with mental health services. Adult B remained under the care of his GP and medication advice was provided to his GP from mental health services. Adult B had a range of prescribed medication for physical health and mental health, which included anti-anxiety and antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia.

6.13 Agencies involved

The agencies involved with Adult B were an adult social worker (Torbay), GP, Accommodation provider and supported living staff, mental health services, Independent Care Act and Health Complaint Advocate, Enabling service for one-to-one hours, police, and the ambulance service.

6.14 Forensic history / Police involvement

Adult B did not have any convictions or cautions. Police had contact with Adult B in 2004, which led to a physical and emotional abuse disclosure in an Achieving Best Evidence (ABE) interview. In 2009, Adult B was reported missing, and police were involved in a child protection strategy meeting because Adult B set up a camera in his bedroom at the residential home that overlooked the playground of a school. In Aug 2019, Adult B made disclosures to supported living staff at the time his mental health had deteriorated, that he wanted to harm himself and had sexual thoughts about children, this was reported to police. In June 2020, Adult B disclosed he had downloaded indecent images of children (IIOC), this was investigated but none were found. A Vulnerability identification Screening Tool (ViST) was completed, outlining the deterioration in mental health, and child protection concern and sent to Torbay and South Devon Foundation Trust single point of contact (SPOC). Adult B was then referred into the Multi Agency Public Protection Arrangements (MAPPA)[12] process. In July 2020 police considered B under the Potentially Dangerous Person Process (PDP)[13]. Adult B did not meet the threshold for MAPPA or the PDP process. The telephone number of a helpline was also given to B called ‘STOP IT NOW’ for people concerned about sexualised thoughts about children.

[9] The Care and Support (Eligibility Criteria) Regulations 2014. An adult’s needs meet the eligibility criteria if—(a) the adult’s needs arise from or are related to a physical or mental impairment or illness; (b) as a result of the adult’s needs the adult is unable to achieve two or more of the outcomes specified in paragraph (2); and (c) as a consequence there is, or is likely to be, a significant impact on the adult’s well-being.

[10] Devon Partnership NHS Trust (DPT) is a mental health trust providing mental health services (adult and older persons) and learning disability services in Devon (excluding Plymouth). The Trust works in partnership with other organisations including Devon County Council, Torbay Unitary Authority and third sector organisations. DPT also works in partnership with other organisations to provide Children and Adolescence Mental Health services (CAMHs)

[11] the process of differentiating between two or more conditions which share similar signs or symptoms.

[12] MAPPA Criteria – Every MAPPA offender must be identified in one of the three categories. Category 1 – Registered sexual offenders as specified under Sexual Offences Act 2003, Part 2: Notification and Orders (on the Sexual Offenders’ Register); Category 2 – Violent offenders and other sexual offenders who are not required to register: An offender convicted (or found not guilty by reason of insanity or to be unfit to stand trial and to have done the act charged) of murder or an offence specified under Schedule 15 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (CJA 2003) Schedule 15 Criminal Justice Act 2003 who received a sentence of 12 months or more or a hospital order; An offender barred from working with children under the DBS Vetting and Barring Scheme (or subject to a Disqualification Order for an offence listed under Schedule 4 of the Criminal Justice and Court Services Act 2000, which preceded this Scheme). Category 3 – Other dangerous offenders: a person who has been cautioned, reprimanded, warned or convicted of an offence which indicates that he or she is capable of causing serious harm and which requires multi-agency management at Level 2 or).

[13] College of policing( Feb 2017 – updated 2020) Although not defined in statute, a PDP is a person who is not currently managed under one of the three Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements (MAPPA) but reasonable grounds exist for believing that there is a risk of them committing an offence or offences that will cause serious harm. a person charged with domestic abuse offences on a number of occasions against different partners but never convicted of offences that would make them a MAPPA-eligible offender, an individual who is continually investigated for allegations of child sexual abuse but is never charged or never receives a civil order, but whom agencies still believe poses a serious risk of sexual harm to children, a person suspected, but not convicted, of terrorism or extremism-related activity, where a community psychiatric nurse (CPN) or other mental health worker shares information with the police that a patient with mental ill health has disclosed fantasies about committing serious violent offences. The patient is not cooperating with the current treatment plan, and the informant believes serious violent behaviour is imminent. a person who has committed offences abroad that, had they been committed here, would result in the offender being managed under MAPPA.

7. Thematic explanation, analysis and findings

7.1 The key events identified were used to evaluate and explain professional practice and capture learning. Relevant research and wider evidence of effective clinical and professional practice, learning from local Devon male suicides, and the National Confidential Inquiry into suicide and safety in Mental Health (NCISH) (2019,2021,2022) formed part of the analysis. The analysis looks at how direct practice unfolded the way it did for each person and considers the factors that influenced practice within organisations and interagency working.

7.2 The care and support of the three men was provided at a difficult time for all agencies. The pandemic impacted on how care and support was experienced and how services in mental health

were prioritised and delivered. Observations made in the analysis are drawn from information provided to the SAR and interviews. Practitioners can only ‘know what is knowable at the time’. Understanding what happened and why requires understanding of the local rationality of professional practice,[14] and “hindsight bias”[15] should be avoided. The LR, upon drawing all the information together, has a window on events from all agency perspectives, allowing reflection on practice and systems through a ‘different lens’.

7.3 Whilst the three men had different individual circumstances, there were a number of parallel themes. These are summarised as trauma, mental health condition (more than one), poor and relapsing mental health, expressed thoughts of suicide, depression, anxiety, history of self-harm and suicide attempt, and excess alcohol use. Other connecting themes was that of communication difficulties at times of high levels of distress, difficulty or declining to engage with treatment or services, and two men had supported living placements where there was a breakdown of this placement with escalating risk. Two men described how they would end their lives and made an earlier attempt shortly before death.

7.4 The following themes listed in the table below were identified in this SAR. Some also feature in other local SARs and in the Local Government Analysis of Safeguarding Adults Reviews (April 2017 – March 2019). These are system problems likely to be repeated in other cases.

| Themes in this SAR |

Themes in Southwest SAR report |

| Direct Care | |

| Mental Capacity – Decisional and executive capacity | ✔ |

| Risk assessment male risk factors | ✔ |

| Carers assessment | ✔ |

| Communication family, referral outcomes | ✔ |

| Mental health relapse | ✔ also found in recent local SAR |

| Engagement with care and support | ✔ |

| Recording – accuracy of information | ✔ |

| Alcohol | ✔ Attention to MH |

| Clinical presentation / Diagnosis incl. Mental health and learning disability | ✔ Attention to MH |

| Self-neglect | ✔ |

| Dual diagnosis | ✔ |

| Interagency Working | |

| Access to mental health history | ✔ |

| Information sharing internally and interagency | ✔ Records sharing |

| People in need not meeting service criteria | ✔ and found in recent local SAR |

| Safeguarding – raising concerns process | ✔ |

| Collation of personal history | ✔ |

| Escalation protocol | ✔ |

| Multi-agency working and cooperation | X |

| Breakdown in package of care with escalating risk | ✔ |

| Interagency working and cooperation | X |

| Over reliance on emergency services for mental health crisis | X |

| Organisational Features | |

| MH resources face-to-face assessment, reliance on emergency services | ✔ Resources/workloads |

| Access to mental health inpatient beds | X |

| Services experienced as not meeting need. Client and staff. | ✔ Personalisation |

| Wait times in ED | X |

| Knowledge – trauma informed | ✔ |

| Access to specialist advise | ✔ |

| Local Authority boundaries | X |

| Gaps in services | ✔ |

| Other | |

| Impact of pandemic on people and services | N/A |

[14] The Local Rationality Principle encourages an understanding of why a decision, action, or error that seems irrational in hindsight, was actually the most rational choice at the time. It helps to understand the context of contributory factors influencing services and provides understanding of events, skills, and constraints.

[15] Hindsight bias is the tendency to ‘consistently exaggerate what could have been anticipated in foresight’ (Fischhoff, 1975) and is well reproduced research finding. Outcome bias is an element of this whereby we judge decisions or actions that are followed by a negative outcome more harshly than if the same decisions or actions had ended either neutrally or well. Blaming bad outcomes on simple causes such as human error can literally seems to make sense because knowledge of the outcome changes our perspective so fundamentally (Woods et al., 2010).

8. Direct work with individuals with care and support needs

8.1 How well the men’s health and social care needs met is explored using the wider terms of reference. The pandemic ran from early March 2020 – February 2022 when all restrictions were lifted, and England returned to the ‘living with covid’ strategy. Mental health need was the main factor in the circumstances of how events evolved. Adult C died at the time the rule of six was implemented for indoor and outdoor gatherings in September 2020, followed by Adult N who died just after the second national lockdown in early November 2020. Adult B was the third man to die, shortly after the third national lockdown in January 2021. Mental health deterioration for two of the men started late 2019, and in mid-2020 for another. This SAR found that during the pandemic the men’s health and social care needs were partially met, with difficulty in engagement and access to mental health services. The was a feature in all cases.

8.2 Generally there are a range of services available and working with men who have complex mental health. Mental health and the Adult Social Care (ASC) act as a conduit for commissioning other services to meet individual needs from a variety of providers and charities. Funding comes from care act funding, some via health funding, (within a reasonable budget), and some are personally funded by individuals with sufficient financial resources. Additional packages of care to provide one-to-one support are available as an add on to core hours in supported living. As a broad description, services work flexibly as multiagency partners. Inter-agency collaboration fluidity and mutual support is reliant upon mental health services having resource and capacity to step up their involvement at times when the support packages need help to continue. Alongside this there is access to out of hours services for mental health support and psychological services for anxiety and depression. There is also access to drop-in centres and help lines, provided by partner agencies and the voluntary sector.

8.3 Health Care is provided via primary care GP services who deliver a range of physical health care and specific health checks, i.e., learning disability annual health check, diabetes monitoring. There are referrals and emergency admission to the general hospital and other health services. Mental health care is provided by the local statutory services Devon Partnership NHS Trust (DPT). This includes adult and older persons and learning disability services in Devon (excluding Plymouth). DPT works in partnership with other organisations including the local authorities, third sector organisations and in partnership to provide Children and Adolescence Mental Health Services (CAMHS). There are dedicated specialist mental health teams and services for first contact and assessment, with provision of a range of out of hours services. Adult Social Care is provided by Devon County Council and Torbay and South Devon NHS Care Trust. These services are for adults for whom activities of daily living can be difficult (because of illness, older age, or a disability) helping them to live as independently as possible. Housing options include affordable housing via home choice, private rental, home ownership, shared ownership/leasehold, shared lives schemes, extra care housing/ supported living, care homes and short-term crisis and respite options.

8.4 Considering the question of what is working well from resources available, taking account of the pandemic, the following observation was made. All services involved engaged well with the role they were commissioned to provide. Adult social care, mental health care, supported living, other commissioned services, GPs, and general health care services all worked well individually. The mental health FRS, assessment service, psychological therapies, drop-in centres, and support services work well in circumstances where the person is motivated and able to use self-direction and reassurance, at times of increased anxiety. Agencies and other services collaborated effectively with mental health services until concerns about deteriorating mental health and a breakdown in the supported living package of care were referred to mental health for assessment, help, and specialist advice. At this point the function of the commissioned services faltered, and Adult C and B risk became unmanageable due to levels of distress and deteriorating mental health.

8.5 In this SAR there were barriers identified by agencies and services. One significant barrier in the care of Adult B, was the inability to access flexible mental health and learning disability services, to gain a comprehensive and specialist assessment. SAR information described that accessing mental health services was difficult. Other comments included that services were criteria focused, with no flexibility for people who do not fit neatly into criteria. Obstacles illustrated included reduced attendance at supported living premises, difficulty accessing face to face assessments and difficulty gaining guidance at times of crisis. Another observation made was that these difficulties were not isolated to the pandemic, but at other times pre pandemic and since. Agencies and services also identified difficulties with information sharing from mental health about history and risk. It was reported that information was difficult to obtain for two of the men, and that this was an ongoing problem experienced with other individuals.

8.6 Services described as missing by those involved included specialist consultation, mental health expertise, and guidance, with access to relevant training and support for partner agencies when working with people who had complex mental health needs. When exploring what service would have filled the ‘gap’ experienced, the service described was one that would attend housing, provide help, advice and support even where individuals were not open to mental health services. The service outlined to the LR best fitted a form of consultation and outreach service. Although there was access to the FRS, this was not experienced as helpful by Adult C and Adult B, or by the services involved. Another service missing was one that worked flexibly with people who had both mental health and learning disability needs. Another gap in services described by mental health managers related to the criteria for accessing talking therapies. To gain the maximum improvement requires Individuals to have a level of motivation. This service does not engage with people who had suicide or self-harm attempts within six weeks as this was considered too high risk, and the service requires alcohol use to be controlled. It was described to the LR that there was a gap between the self-access crisis services and talking therapies where people fell through the gap.

8.7 Conversely, in response to the gaps identified and the services described as missing, mental health services identified a disparity in their funding, and commissioning arrangements affecting what and how services can be delivered.

8.8 Generally from material provided to the SAR, and observations made by those involved, when thinking about improvements in support, the main comment was the difficulty experienced in accessing mental health services. The views expressed included improvement was needed for more face-to-face contact, and more flexibility to be responsive to people using services. GPs identified the need for more consistent and easily accessible ways of discussing mental health needs for people supported by primary care. Escalation protocols for fast and timely discussion about distressed individuals who fall outside of service criteria were needed. This was defined as a protocol with the power to ensure that services and agencies work together to respond promptly during times of crisis, even when there is disagreement among agencies, and when the circumstances do not align with the current safeguarding adult escalation policy.

8.9 Adult social care’s IMR for Adult B, identified improvements were needed in consultation and education, for communicating with someone when they are in a state of distress. Adult B was making genuine pleas for help, and the response to such pleas was considered more important than establishing whether the person fitted service criteria. Comments were made, that if services such as mental health cannot offer case management, can they offer robust consultation for adult social workers and care staff in terms of risk management and care planning?

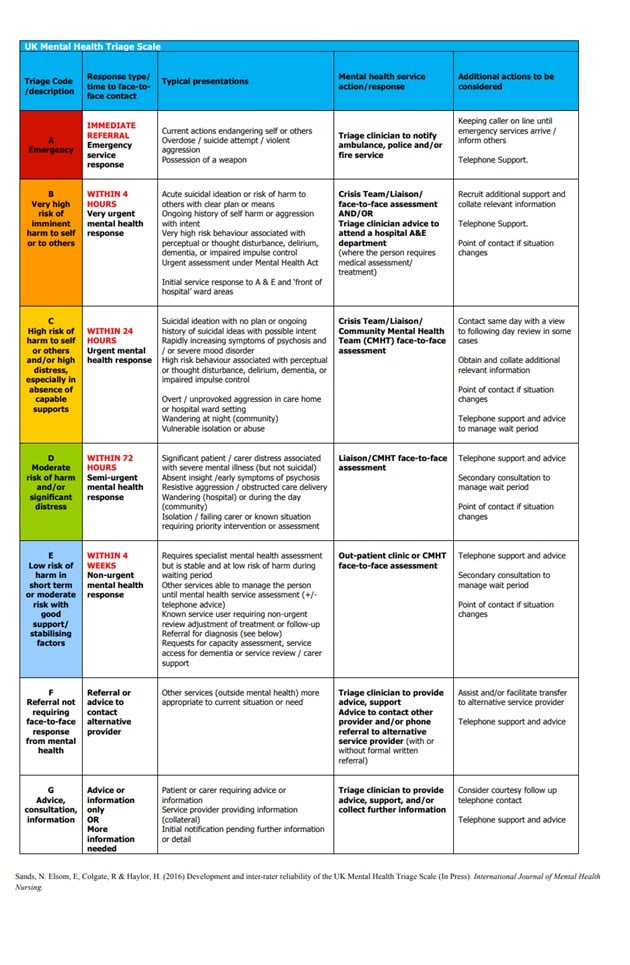

8.10 Services were addressing the needs of this group of men via the usual organisation operational policies and protocols. Services work in partnership with statutory agencies commissioning other support services as required and using sign posting to voluntary, community, and social enterprise VCSE[16] sector services where this is indicated. The aim was to keep the person as independent as possible and for them to remain in their own homes. Adjustments were made to service delivery during the pandemic as per government advice. Devon mental health services brought forward plans for the Access and First response service (FRS) to have a service 24/7. This service was introduced in March 2020 as phone-only, with referral onto other services for face-to-face assessment. There was a triage function and outcomes ranged from telephone support or onwards referral to another mental health team, psychological therapies, or other relevant support options.

8.11 As a rule, services engaged with people who present with distress and active thoughts of suicide as was indicated in line with their agency purpose, policy, and procedures. Assessment of need and risk was undertaken at the time of contact, with referral onto other services as indicated For each man, practitioners involved responded to distress and active thoughts about suicide as the person presented face to face or via the telephone. Practitioners used the tools and structures of their services, policies and procedures, both single and multi-agency, for example referring into adult safeguarding with concerns about risk to self and children. On a day-to-day basis practitioners worked in partnership with the men using their care plans, risk assessments, and knowledge of the person. Staff also used therapeutic relationships, de-escalation techniques at times of distressed and disturbed behaviours. When needed practitioners and care staff requested and implemented advice, shared concerns with other agencies, sought supervision, and asked for help.

8.12 Examples of good practice for engagement with the men are seen in the interactions from supported living, the adult social worker (Torbay), and mental health services, who were kind and compassionate in response to distress and behaviours in the most difficult circumstances. Supported living staff were innovative in dealing with a situation involving risk to others using distraction and offer of activities. The Crisis Resolution Home Treatment Team (CRHTT) in May 2020 were able to engage well with Adult B which resulted in an improvement in mood, reduction of anxiety and agitation. Care staff and GPs followed care plans and tried to distract Adult C and B using techniques identified by the men themselves and mental health service advice. GPs in their contact with Adult C, B and N also used the distraction and relaxation and encouraged the men to use these techniques.

8.13 There was good practice from all agencies in contact with the men in their ability to engage with very distressed individuals to gather the appropriate information from them at a difficult time. There was kind and compassionate contact and engagement with Adult N and Adult C shown by ambulance staff on their attendance. Ambulance, police, GP and supported living were able to engage the men in discussion about thoughts and plans to end their lives. ED staff were able to engage with Adult B and facilitate his assessment by liaison psychiatry at a time of massive demand on services. The adult social worker (Torbay) was practical at times of distress and when B got a new phone, care staff were asked to input the telephone numbers for out of hours support. In March 2020 the adult social worker was advised by care staff that Adult B was verbalising thoughts about jumping from the building. In response to this the adult social worker undertook a face-to-face visit with B, although at the time he was not an active client on the case list, however the knowledge and relationship the adult social worker had with Adult B was the conduit to the follow up. The adult social worker used processes to engage Adult B to enable him to have some control and influence in events, and in the review of his package of care, this was good practice. The adult social worker liaised with the GP, and explored ways to help B communicate how he was feeling, although communication aids were refused. Supported living were responsive and flexible, attempting to meet the needs of these men and respond to their increasing levels of distress with kindness and structured support.

8.14 Largely the engagement approach was person centred and flexible, taking account of the presentation and situation at the time. There are a range of examples of good practice in person centred and flexible approaches. The ambulance crew used their own assessment of Adult C, who they assessed was not safe to leave at the accommodation when mental health staff advised he would be safe to leave as he was waiting for a support visit. The ambulance service responded to calls, made contact, face-to-face and telephone, attended the home address, spoke with the men, carried out physical health assessment, mental capacity assessment and conveyed them to hospital when this was indicated. In the circumstances of Adult N, information provided, suggests the contact with ambulance staff was more conducive to Adult N talking about the situation. When contacted, the police responded to each man as per their processes relevant to the presenting issue. The police had a number of face-to-face encounters with Adult C and Adult B, which were person centred, proactive, responsive and respectful, and support was provided to care staff. On the day Adult C died, an officer stayed at the home address due to the agitated behaviour, allowing the staff on duty to make calls to mental health services and GP for crisis advice. This was good practice and evidence of interagency cooperation.

8.15 There was good practice from mental health staff working in FRS, who attempted to engage with the men when they called the service expressing distress. Responding to someone in these circumstances and making an assessment during such a telephone call, is often difficult. When the call was ended by the men, staff contacted relevant other agencies to hand over information. Mental health services were also person centred in providing contact details for out of hours support for Adult C, B and N. The supported living staff were aware of individual need, their difficulties and provided support, prompting, enabling, made referrals as required, and facilitated reviews with key agencies.

8.16 GPs involved were flexible, and person centred. Primary care systems often led to appointments with the GP available on the day of appointment rather than a dedicated GP. For these men, the GP who had the most contact with them, responded to calls from staff and Adult C, B and N in the main. This was good practice. In Adult B circumstances the GP in telephone consultations did manage to engage with B despite communication limitations. This is evidenced by B initiating contact with the GP when in an agitated state. Other primary care health needs and risk were also responded to flexibly i.e., when the GP Phlebotomist service raised concerns about B’s intimidating behaviour at the surgery, a male health care assistant attended B’s accommodation to take bloods. This was good practice. Good practice was seen in response to Adult B’s physical health needs, managed via the GP and general hospital. Care included ongoing monitoring and responding to acute problems and when admitted to hospital learning disability nurses provided support, this was good practice and a person-centred approach. Another example of good practice in person centred, and flexible care, was the input from the advocate. It is noted that the commissioned advocacy service did not hold an NHS complaints contract for the Torbay locality, however the advocate continued to help with because of their knowledge and relationship built up with Adult B.

8.17 Although there were many examples of good practice, the three men had mixed experiences of person centred and flexible approaches to their care needs. Agencies responses to the pandemic required prioritisation of resources and some changes in the way in which services were delivered, taking account of Government Covid 19 direction and advice, although Adult social care (Torbay) describe maintaining interventions throughout the pandemic to meet legal duties. The need to prioritise resources specifically impacted on mental health support.

8.18 Adult B experienced inflexibility to his care needs because of his perceived cogitative difficulties. Internal referrals for Adult B were made by adult mental health to the learning disability service, and these bounced back as an inappropriate referral, at a time of acute distress and deteriorating mental health. In the IMRs and in discussion with relevant managers and staff, views were expressed that mental health services were less person centred with Adult B. Views were expressed by those who knew him, that he needed more time to take on board what was being said and time to respond. The LR considered outcomes from mental health was in part, as a result of contact with B where he was unable to respond quickly to questions, and on the requirement to prioritise responses to all the referrals made to the service. Individually there was limited flexibility from mental health services at the time of contact with the men, although the introduction of FRS and its ethos was flexible, and person centred. This was a crisis line for people to use when they felt they were in crisis and did not require a professional referral.

8.19 The LR analysed the key events identified in the chronologies see Appendix 2,3, and 4 with footnotes. The men’s mental health needs were the primary factor in their circumstances, as evidenced by the key events and their unfolding. The men’s perception of their needs differed to that of mental health professionals. This is not unusual, although the LR comments the levels of distress for each man, especially for Adult C and Adult B were severe.

8.20 There were various contributory factors to the difficulties in mental health care which impacted on how care was delivered, and how the men engaged (or not). With the advantage of knowing the outcome of events and looking at agency information together, the following influenced events and actions. These are seen throughout this report as the emerging themes and are clustered into categories. Individual patient factors – engagement in treatment and refusal of services, excess alcohol use, communication, mental health relapse, mental capacity – decisional and executive, and self-neglect. Operational factors – mental health resource, the impact of the pandemic on people and services, the demand on mental health services, the need to prioritise urgency, limited ability for face-to-face assessment, service criteria, gaps in services, and breakdown in the support package during crisis with escalating risk. Risk assessment – accuracy of information, information sharing, collation of history, different agency perspectives, perceived protective factors, verbal assurances of no plans to self-harm and key information unknown to mental health services. Multi-agency working – knowledge and skills of staff, and interagency cooperation.

8.21 Adult C wanted hospital admission to ‘fix his body and brain’, although it is not clear if his focus was on psychiatry or physical health care. His care and intervention were experienced through the lens of dependant personality disorder[17]. Admission to hospital was considered as not indicated during times of crisis as he was perceived as lacking in confidence to take personal responsibility. At times when C was in a state of heightened anxiety and refusing to take anti-depressant medication, he was unable to be reassured. Mental health services have a commitment to work in partnership with people with personality disorder in structured ways, sadly Adult C was not able to do this during his crisis. Upon reflection services appeared distracted and overly reassured by the package of care in supported living and one-to-one enabling services. Adult C’s needs from his perspective were not met.

8.22 The mental health IMR for Adult C includes his diagnosis as dependant personality disorder, an anxiety, acute stress reaction, and moderate depressive disorder. The consultant psychiatrist’s witness statement for the coroner’s inquest documents further information, that of a diagnosis of a recurrent treatment resistant depressive illness with atypical features and complex presentation with dependant personality traits, fear of coping alone, and a pattern of expressing suicidal thinking as a way of communicating his distress. It was unknown if the personality traits were lifelong or caused or exacerbated by his long experience of illness. The care coordinator included in information to the coroner that Adult C experienced severe depression with psychotic symptoms, suicidal thoughts, anxiety, and an inability to cope. The rationale for the primary focus on dependant personality disorder in C’s care is not clear. Without more information, understanding the events in the context of the level of distress, mental health crisis, C’s views about medication, and whether these were delusional in their intensity, is difficult.

8.23 There was treatment for alcohol detoxification in Nov 2019, and further concerns that Adult C was using alcohol in the months before his death. The SAR was not provided with information about exploration of the later alcohol use. The care coordinator reported he spoke about poor memory, that he was agitated and believed his brain was damaged. In January and February 2020, he stated he thought he had dementia. Adult C made multiple daily statements that his brain and body was not working properly. In a past hospital admission (2017) with a similar presentation, Adult C was admitted to the older persons mental health ward. It is not known whether dementia was a clinical consideration in this admission. Concerns about his brain not working was a longstanding concern. The brain scan in 2017, repeated in May 2020 did not provide reassurance. The 2020 scan results showed some evidence of a previous stroke and “a degree of cerebral atrophy greater than expected for age, but no significant change from a previous scan”. The LR comments on information provided to the inquest, that by the summer of 2019, Adult C couldn’t deal with everyday life. Adult C is described as making the same statements about medication, every time new medication was prescribed, he stopped taking it, he was restless, pacing, unable to sleep at night, he lost interest in activities he once enjoyed, followed his partner everywhere, and that he depended on her too much. The GP in the summer of 2019 referred C into mental health service with low mood and memory problems. The NHS website includes information about common changes to behaviour with onset of dementia. The LR is not making a diagnosis, but comments on the similarities which make interesting reflection of the reported behaviours, acknowledging dementia was a concern for him.

- loss of memory and thinking skills.

- repeating the same question or activity over and over again.

- restlessness, pacing, wandering, and fidgeting.

- night-time waking and sleep disturbance.

- following a partner or spouse around everywhere.

- loss of self-confidence, which may show as apathy or disinterest in their usual activities.

8.24 Adult B was consistent with thoughts about suicide and mental health deterioration since August 2019. Adult B is noted to be a risk to children. There was concern expressed about his behaviour around local schools, this was identified in agency reflection as a distraction for mental health services and it impacted on assessment of need. There is an assumption made that B’s distress and anxiety is because of the police investigation into IIOC on his computer. The chronology outlines the deterioration in mental health and distress started some time before this. Adult B’s limited communication and inability to engage in psychological therapies, due to learning disability, is the reason given as to why there was no alternative service to offer. Adult B also had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and he described hearing voices. Thought blocking, and poverty of thought are negative symptoms of schizophrenia, this may have been a factor in his inability to communicate. Staff describe he would start a conversation, there would be a long gap before he spoke, and he appeared to be listening to something. In February 2020, the GP made a referral into mental health services and an outpatient appointment for March 2020 with a consultant psychiatrist for a medication review was offered. This appointment was then cancelled due to the pandemic and the need to concentrate on urgent referrals. This was a missed opportunity to consider the full picture of his mental health. In May 2020 Adult B had an episode of care with the CRHTT. The team record a longstanding mood disorder with possible psychotic overlay at times, with OCD component, recent deterioration in mood with exacerbation of OCD, intrusive thoughts and increasing distress. When discharged nineteen days later the team note there is significant improvement in mood and reduction in anxiety and agitation, with no psychotic or delusional symptoms elicited at discharge. Another potential influence to deteriorating mental health was Adult B’s diabetes. It was known that B was not monitoring his blood sugar accurately a few months before his death.[18] A review of Adult B’s physical health was advised in September 2020 in the MHAT assessment, which ended before conclusion, due to distress. It is unknown whether his diabetes was reviewed, and if there was any link to his deteriorating mental health considered.

8.25 As the CRHTT intervention was successful in improvement of Adult B’s mental health, it is not understood why with a significant mental health diagnosis, that mental health could not offer a service. At the same time as Adult B’s cognitive deficits were highlighted as the reason that mental health are unable to provide a service, Adult B is then signposted to online and community resources with the NSPCC and the Lucy Faithful Foundation (LFF). These resources are for people who have concerning thoughts about harming children. Both resources require Adult B to cognitively engage in therapy, which appears incongruous, given Bs cognitive deficits are a barrier to accessing mental health services.

8.26 The focus of care and intervention for Adult N was the excess alcohol use and his mental health was viewed through this lens. He told his mother that he would have liked an assessment by mental health services rather than being sent home, although while at ED, he declined assessment. Equally local drug and alcohol services did not show curiosity to the number of referrals and attendances at ED. The level of depression was not explored further after discharge. Adult N told the ambulance and ED staff, he was not taking medication for depression, but told the GP he was. Adult N disclosed more information to ambulance staff, wanting to die, wanting to sleep and not wake up, relationship breakup, being lonely, and no access to the internet. There were concerns about self-neglect. Adult N verbally reassures services he knows how to get help but did not or was not able to follow this through. This raises the question of whether this was related to reduced motivation and mental capacity, due to the depth of his depression and, or alcohol use? His mother described at inquest that since the pandemic there was a decline in his mental health, and he was consuming large amounts of cider a day. There was no detail to the levels of alcohol consumed in the assessments made in ED,

8.27 The collation of personal and mental health history is a theme in this SAR. History, and personal information about Adult N, C and B appears unknown to mental health services. The mental health IMR notes that Adult Ns first contact with services was in 2017. Earlier contact from 1993 for severe depression with psychotic features and four episodes of treatment for depression and anxiety in later years from 2008 to 2014, is not referred to. There was limited information about his social history, the breakdown of his marriage and no detail about his employment history, and why he has not worked for a significant time. Key information was unavailable to mental health staff. It cannot be known this information would have changed the assessment and intervention, but this is significant to risk assessment context. In Adult C’s care, important background history prior to his first mental health contact was not known. Family recall that his mental health significantly deteriorated after the death of a parent, describing he was never the same man again. Details of this information generate questions about trauma as a child and information might indicate other siblings were affected. Relatives of Adult C’s raised questions about information discussed at the inquest that was not included in the IMRs, that of the consideration of autism and a request for supported living to undertake an online autism assessment. There was no further information about this available.

8.28 Another example of unknown information is the assessment of Adult B in 2008, which concluded that he was not eligible for an ongoing learning disability (LD) service due to the low level of impairment. The mental health IMR makes no reference to this and may account for why internal referrals were made to LD services. This is potentially a systems problem related to history taking and, or access to past mental health records. In June 2020 Adult B is described in a letter from mental health services to the GP as having a borderline learning disability, with possible diagnosis of autism. There was no other information about this, and autism did not feature in the information provided to supported living, nor was the adult social worker aware of this information.